The Fragmentation of Black America

Rethinking the way appeals to understanding racism in America assume a solidarity within the Black community that may be gone.

In our current sequel to the Gilded Age, a Silicon Age defined by technological dominance and staggering inequality, it’s becoming increasingly clear that the early 20th century may have been America’s true face, while the post-World War II boom was a temporary high mistaken for a permanent ascent. The backlash to that era's social and political advancements has not only squandered that moment but reshaped our society into something colder, harsher, and more unforgiving.

Within this framework lies an inherently American classism, driven by access to capital, education, travel, professional networks, and the much-debated access to the social currency known as “Whiteness.” This last indicator is particularly complicated to define as backlash grows not only from socially conservative and moderate White Americans but also increasingly from Americans of color who see the language of racial justice as elitist or out of touch with material reality. This raises a pressing question: Does the framework for discussing race in America even work anymore?

For Black Americans, having introspective conversations about problems within our community is a risky venture because such discussions are quickly twisted and co-opted by bad-faith actors or those lacking the imagination to understand how deeply racial hierarchy runs through American history and identity. Reactionaries are eager to ban conversations about race altogether, while those deemed “reactionary centrists” (dubbed this by younger, independent scholars) have been known to use selective observations to cast doubt on the undeniable truth of racial quality-of-life gaps, as in homeownership, incarceration rates, maternal mortality, educational attainment, and voter suppression. This piece is not an invitation to foster intellectual laziness or serve as ammunition for those who believe racial disparities are mere exaggerations or distractions.

Yet, we must confront a hard truth: Black experiences are arguably more fragmented today than ever. While wealth disparities, regional classism, and quality-of-life gaps have always existed in Black American life, there was once a more unified struggle against a society that openly (not subtly) raped, beat, segregated, economically sabotaged, and outright terrorized an entire population based solely on skin color. This shared experience of being denied entry into establishments forged a powerful solidarity amid staggering inequality.

But today, the lines are blurred.

The brutal clarity of de jure segregation (state discrimination by law) has given way to the insidious reality of de facto segregation (state discrimination by fact), a system where social and economic disparities persist through bureaucratic neglect, privatization, and the retreat of public investment.

So, I am sharing with the Nothing New community my evolving thoughts on how race is being handled and where I may now disagree with my former self, especially in light of the social and political upheavals of the last eight years.

Inequality’s Shadow

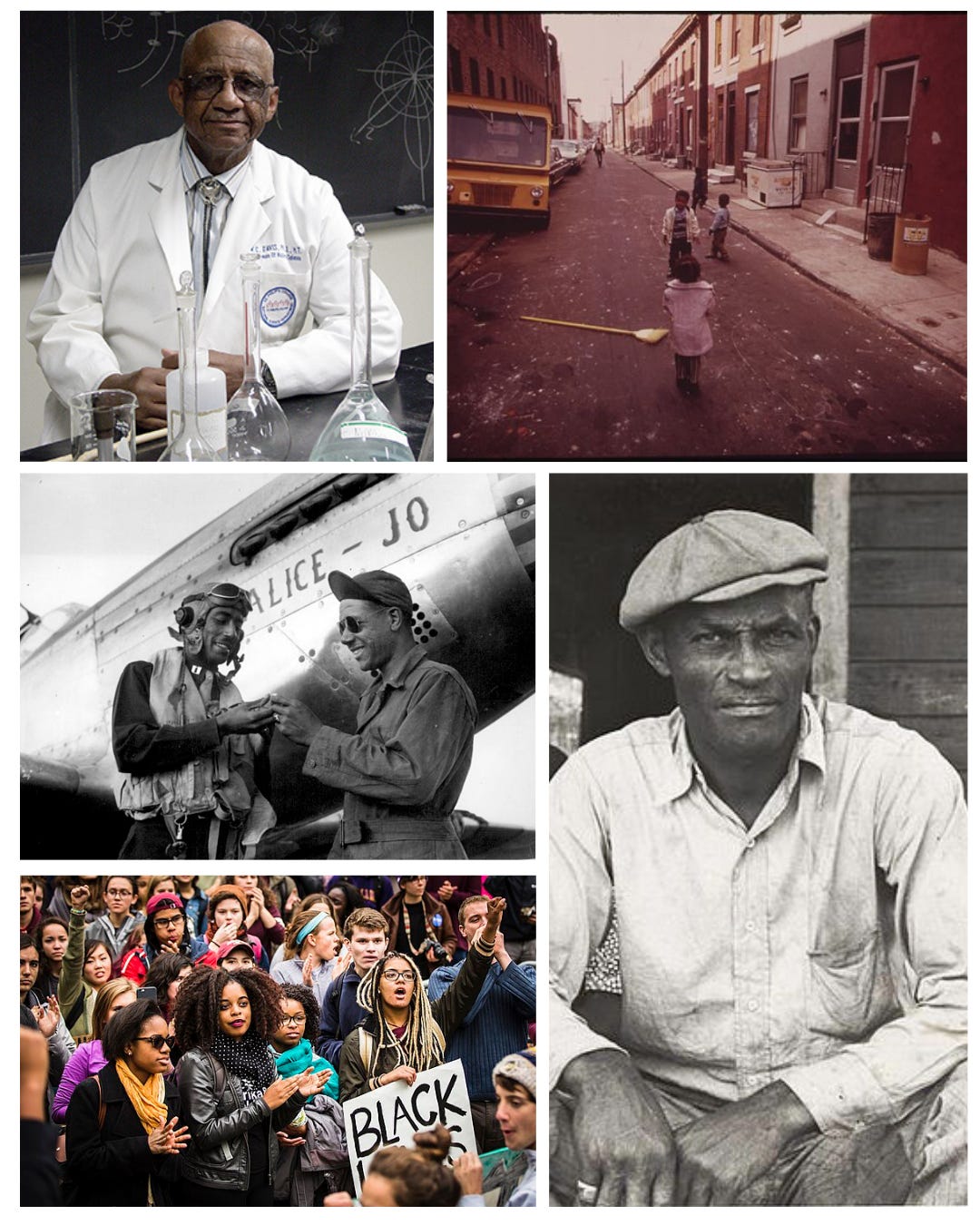

Most scholars and readers familiar with the landscape of Black intellectual thought recognize the legacies of W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington. Both men emerged as towering figures at a time when the Black experience was slowly distancing from the immediate traumas of slavery. That divergence was symbolized by Du Bois, who was never born into slavery and was raised in a part of America (Massachusetts) that, while still harboring racism, expressed it in subtler ways compared to the violent suppression of the South. Du Bois’s upbringing in a region that valued education and embraced relative modernity informed his belief that the path forward for Black Americans lay in cultivating a “Talented Tenth,” an educated Black elite that could leverage liberal arts education to advocate for systemic change and uplift the broader community. Du Bois co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1905. Du Bois’ appeal was considered militant for the time and drew in Northern Black academics and younger activists not carrying the same scars as their elders.

In contrast, Washington was born into slavery in the American Deep South, a region still smoldering from its defeat in the Civil War. During his lifetime, the South was already engaged in mythologizing its loss as a 'noble cause' rather than a brutal defense of human bondage. This falsified history laid the foundation for the continuation of a modern oligarchy where the masses remained under the thumb of a small, entrenched elite and distant financiers. Yet, the rage generated by this exploitative system was irrationally and violently turned against Black people instead of the true architects of Southern deprivation.

Navigating this harsh reality, Washington focused on incrementalism and practical survival. He believed the best path forward was through Black self-sufficiency and vocational training, as exemplified by Tuskegee University. For Washington, economic empowerment through skilled labor and institutional autonomy represented the most realistic route to Black advancement in a society actively working to keep them marginalized.

Du Bois understandably viewed Washington’s approach as excessively accommodating to oppressive power structures. To him, Washington’s strategies seemed like a resignation to subjugation rather than a meaningful challenge to it. And for what it’s worth, Washington’s approach was more palatable to White Americans, even earning him a trip to the White House when the first Roosevelt occupied the Oval. On the other hand, Washington saw Du Bois’s lofty intellectualism as detached and elitist, removed from the brutal daily realities faced by those still entrenched in poverty and subjected to unaccounted for systemic violence. Despite their differences, both perspectives laid the foundation for competing visions of Black healing, advancement, and survival in a nation that structurally and culturally despised them.

The tensions between their approaches are vividly displayed in their most famous works: Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk and Washington’s Up From Slavery. Together, their writings capture two ideological streams that continue to influence debates around Black progress today, especially in fields like education, economic independence, and cultural resilience.

Fragile Progress

In the past, I would have championed Du Bois’ vision over Washington’s while acknowledging the significance of both approaches.

As the Civil Rights Movement expanded nationally, direct action, confronting injustice rather than accommodating it, became the central catalyst for change. However, framing their legacies solely through that lens overlooks the deeper complexities and symbiotic nature of their respective strategies.

Du Bois’ emphasis on intellectual rigor and cultural autonomy laid the groundwork for psychological and ideological resilience. A fortitude that proved essential for African Americans navigating predominantly White institutions and enduring the microaggressions and passive-aggressive racism of the North. His Talented Tenth model aimed to cultivate a Black intelligentsia capable of articulating systemic grievances and translating them into cohesive frameworks for structural change using law, history, and social science. It also offered a language of empowerment that rejected the infantilization of Black intellect, instead insisting on cultural and intellectual sovereignty.

In contrast, Washington’s focus on economic self-sufficiency and skill-building fortified grassroots community-building efforts. His approach laid the foundation for survival strategies for those operating in the Jim Crow South and those migrating North and West in pursuit of industrial jobs. By promoting economic empowerment, Washington fostered mutual aid and entrepreneurship networks, providing Black communities with tangible, if limited, pathways to stability within a hostile and exclusionary society. His emphasis on practical education and economic resilience also laid the groundwork for a communal ethos that would prove essential during future organizing efforts.

Both frameworks significantly shaped the broader struggle for Civil Rights during the 1950s and 1960s. Washington’s community-building networks became vital during economic boycotts and organizing campaigns, while Du Bois’ intellectual framework empowered a new generation of Black leaders to wield academic rigor and direct action as complementary tools. These movements often intersected as leaders trained at predominantly white institutions in the North or HBCUs in the Mid-Atlantic and South forged connections that transcended regional boundaries. This shared sense of purpose created a powerful solidarity capable of challenging the institutional racism of the Jim Crow era.

Yet the solidarity of the Black experience in the mid-20th century, remarkable as it was, never fully resolved the class divisions temporarily subsumed by the existential threats of disenfranchisement and racial violence. The movement’s early leadership largely emerged from the Black upper and middle classes, reflecting Du Bois’ Talented Tenth model. However, as the struggle broadened to encompass economic justice and anti-imperialism, more radical leaders from working-class and economically marginalized backgrounds pushed the movement’s agenda toward more profound, more systemic critiques of American power.

By the late 1960s, the optimism and unity that had defined Black American solidarity, and, to a lesser extent, broader American solidarity, during the March on Washington had fractured under the weight of deepening insecurity, fragmentation, and disillusionment.

Reactionary forces exploited these fractures, co-opting the language of Black advancement to justify their opposition to further progress. Economic downturns of the 1970s, White flight, and the redirection of political energy away from civil rights toward neoliberal economics ended up creating a bleak landscape for Black communities. Conservative forces seized this moment, not only dismantling hard-won gains but also reframing Black progress as a problem of cultural deficiency rather than structural inequality.

Ultimately, the philosophical divide between Du Bois and Washington was never fully reconciled; instead, it was transformed and carried forward by successive generations. Their legacies reflect a tension central to the Black American experience: the struggle to balance intellectual and cultural sovereignty with economic survival within a hostile society. Today’s debates over Black empowerment, self-determination, and social justice continue to echo the unresolved questions posed by Du Bois and Washington, demonstrating that their battle was never simply about differing strategies; it was about the survival and dignity of Black life in a nation built to deny both.

A Fractured Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard

The broken promises of racial progress are perhaps best symbolized by the countless Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevards crisscrossing America, streets intended to honor a legacy of justice and equality but often marred by poverty, neglect, and decay. It manifests the world ahead for Black America after its civil rights high point.

As philosophical debates continued within the Black community, the broader American society found its own way of contending with Black progress. The racial backlash of the late 20th century became a volatile force within American politics, skillfully masquerading as principled conservatism. As segments of the Black community integrated into schools and workplaces within the broader, predominantly White society, reactionaries exploited this progress to fracture Black solidarity. While integration was necessary to address America’s profound moral failures, it was also a patchwork solution marketed to the world as proof of American progress. Yet, the deeper structural inequities were left to fester, unattended and unresolved.

The impact on the Black community has been bittersweet. As Black wealth has gradually increased, so too has the class stratification that polarizes the lived experiences of Black Americans. On one side are those who have managed to access opportunities within government, business, science, culture, and academia; on the other are those trapped in a working-class death spiral where poverty, inadequate education, neighborhood violence, and mass incarceration remain persistent threats. The economic devastation unleashed by conservative backlash echoes the same structural harms Black Americans faced during the early 20th century, now reframed through the language of free markets, personal responsibility, and colorblind meritocracy.

Ironically, the conservative movement’s anti-government, colorblind rhetoric provided a convenient framework for reactionaries to exploit. Today, so-called principled conservatives express shock at how their movement has been so easily co-opted by forces that prefer a feudal racial hierarchy over the unstable multiracial democracy they have inherited. Yet this takeover is not an aberration but a logical consequence of the same ideological framework they nurtured. The movement’s success in undermining the gains of Brown v. Board of Education, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 is not incidental but foundational to its ideology.

The Supreme Court’s rollback of affirmative action and voting rights through Trump-appointed justices marks the culmination of a decades-long assault on civil liberties. This campaign, cloaked in the language of “fairness” and “meritocracy,” has always been about preserving racial hierarchies under the guise of protecting individual rights and resisting so-called “big government.” Thus, the reactionary capture of mainstream conservatism, built upon a narrative of anti-government and colorblind dogma, has ensured that the progress of the Civil Rights Movement remains perpetually vulnerable to reversal.

Ultimately, what conservative reactionaries and their so-called principled counterparts fail to acknowledge is that the very rhetoric they embraced was always designed to preserve inequality. By denying the legitimacy of race-conscious policy and insisting on colorblindness as a moral ideal, they have only reinforced the power structures they claim to oppose. The result is a nation whose racial progress remains fragile, forever teetering between advancement and regression.

But now we live in a world where this revanchist and arrogant project succeeded and reaped devastation on the Black community in irreparable ways. Before, I would err on the side of trying to rebuild the old world. But now I’m considering the possibility that this pre-conservative movement status quo is gone forever, and with that goes the unique circumstances that enabled community-wide solidarity against a common threat.

Degrees of Separation: Black Progress and the Widening Class Divide

Over the past several decades, Black college attainment, homeownership, and income have steadily increased. While these gains still drastically lag behind those of White Americans and other ethnicities, they nonetheless reflect the broader prosperity the nation experienced, even for its most marginalized groups. The legislative victories of the Civil Rights Movement did create new opportunities for younger generations coming of age during its nationalization or in its wake. Unionized factory jobs, government employment, and, to a lesser extent, professional industries became more accessible to Black Americans as the legal environment shifted and elite institutions were pressured to diversify.

From the 1950s through the early 1970s, government jobs emerged as a particularly vital pathway to Black economic mobility. By 1975, roughly 20% of Black workers were employed in the public sector, compared to about 14% of White workers. This was significant because government employment offered more stable wages, benefits, and protections against discrimination than the private sector. During this period, the Black middle class expanded, creating a growing cohort of professionals, bureaucrats, and educators who formed the backbone of the Talented Tenth Du Bois envisioned.

Yet, the prosperity generated during this window of opportunity was always precarious. America’s postwar wealth began to stagnate due to the costly war in Vietnam, inadequate tax hikes to support newly established social programs, and the gradual decline of the manufacturing sector. The economic upheaval of the 1970s—marked by stagflation, deindustrialization, and the weakening of unions, hit all Americans hard. But Black Americans were particularly vulnerable due to their disproportionate employment in manufacturing and government jobs, sectors where middle-class stability had been built and nurtured.

According to Brookings’ Black Wealth is Increasing, but So is the Racial Wealth Gap, while Black wealth has grown over time, the racial wealth gap has only widened. Structural forces continue to undermine the ability of Black families to accumulate wealth at the same rate as their White counterparts. As factory closures and union weakening stripped economic security from working-class Black Americans, the educational divide between Black Americans with college degrees and those without grew exponentially. The report highlights that while Black Americans with college degrees have made modest gains, those without are increasingly left behind, creating a class rift that mirrors broader American economic inequality but with even fewer institutional safeguards.

Moreover, the Inequality Is High Within the Black Community report by the People’s Policy Project underscores how wealth inequality within Black America is not only persistent but also worsening. The wealthiest 10% of Black families now own 75% of Black wealth, while the bottom half collectively holds less than 2%. This stratification reveals how, even as a small segment of Black America has ascended into the middle and upper classes, the vast majority remain locked out of economic security. The report finds:

The median wealth of the Black poor equates to just 1.5 percent of the race-wide median. At the other end of the spectrum, the Black upper-class possesses a median wealth 19x greater than the race-wide median. If we compare the top and bottom, we find that the Black upper-class has 1382x as much wealth as the Black poor.

As the economy became increasingly hostile to Americans without college degrees, Black elites fortified their positions by acquiring educational credentials and accessing networks necessary to weather the coming economic storms. However, the success of this emerging Black professional class has made the class divide more apparent and, in some ways, more painful. Class distinctions within Black America are no longer just remnants of the post-slavery social order; they have been amplified by policies and economic realities that disproportionately harm those with less access to capital, education, and political influence.

Even as America markets itself as a multiracial democracy in the modern era, the deepening internal divide within Black America reflects the structural cruelty of a system that continues to deny most Black Americans access to genuine economic empowerment. As more Black elites enter mainstream society and gain institutional power, the gap between them and the working class they claim to represent grows starker. This widening gulf undermines solidarity, leaving more people vulnerable to reactionary exploitation and hollow promises of prosperity.

The Red Baseball Cap: Fractured Solidarity and Political Estrangement

The fracturing of lived experiences, and thus solidarity, reflects a deepening division in how Black leaders and communities envision the path forward. Today, Black leaders occupy more direct positions of power and influence within business, politics, and elite culture. But this hard-won progress has also intensified divisions within Black America, complicating the very framework earlier generations of leaders like W.E.B. Du Bois, Booker T. Washington, Roy Wilkins, Fannie Lou Hamer, and John Lewis once operated within.

For those who successfully bridge the gap into a larger, integrated society, the experience often requires the same kind of cultural and behavioral code-switching that immigrants or working-class rural people navigate when entering elite or cosmopolitan environments. Unlike the past, where legal segregation clearly delineated the oppressor and the oppressed, today's economic mobility is increasingly dictated by access to higher education—or more accurately, the networks and institutional affiliations it provides. As economic mobility becomes more dependent on credentialed spaces, the detachment from the lived realities of those outside these hubs of privilege grows ever more pronounced.

In our current era of structural and behavioral racial discrimination, distinct from the overtly legal, on-the-books racial discrimination of Jim Crow, systemic inequality persists, though its face and form have grown more diffuse. This reality is particularly harsh for Black working-class people who, while enduring the same economic precarity as other working-class Americans, experience that hardship through the compounded lens of racial exclusion. Today’s inequity is even more insidious because it has become harder to name and confront within mainstream society. As economic disparity widens, even within Black America itself, the solidarity that once characterized the Civil Rights Movement has become a far more fragile thing.

Nowhere is this fragmentation more apparent than in politics. The Democratic Party, long considered the political home for civil rights advocacy, labor protections, and government accountability, is increasingly losing credibility among its own voters. By leaning into a neoliberal consensus that has exacerbated inequality, while embracing a neoconservative foreign and domestic framework of high defense spending coupled with cutting and privatizing social services, Democrats have alienated much of their base. The past decade’s failures in crucial voting rights and civil rights battles have left Black voters questioning their ties to a party that seems to have traded genuine reform for superficial gestures of progress.

Even more damning is the party’s inability to effectively counter a hostile and unstable demagogue who has weaponized racial and gendered rhetoric against them. Rather than confronting this threat directly, Democratic strategists have often retreated into a colorblind, hawkish approach that depresses turnout and distances them from the communities they claim to represent.

This political estrangement has created an opening for pockets of Black male voters to flirt with the power dynamics of the moment, lured by cartoonish appeals to strength, material wealth, and rugged individualism. While this segment of voters remains too small to suggest a significant realignment, their existence reflects a broader sense of frustration and political disillusionment. The appeal is rarely rooted in serious policy critique but rather in emotional satisfaction—a desperate search for power and agency within environments that repeatedly reinforce the importance of those traits.

One of the most troubling outcomes of this growing fragmentation within Black America is the widening gulf between those who have successfully integrated into mainstream society and those who remain trapped within systems of exploitation and decay. Today’s Black elites often occupy worlds of safe neighborhoods with adequate school systems; if not, they place their children in private schools. They attend professional conferences, travel freely, and leverage networks that provide them with easier access to opportunities. Meanwhile, the Black working class disproportionately struggles to achieve upward mobility. Many who cannot make the climb remain mired in systems of environmental poisoning, violent surroundings, systemic illiteracy, food deserts, and predatory lending.

The outright degradation of living conditions leaves some Black Americans vulnerable to political appeals framed around hypermasculine strength and promises of material wealth, two traits perceived as essential for survival in America’s most neglected and violent neighborhoods. This desperation has contributed to a small but notable movement of disillusioned Black men gravitating toward MAGA rhetoric. For some, systemic critiques of racism and inequality feel abstract and insufficient for addressing their daily struggles. For others, the appeal is rooted in deep-seated misogyny or a broader cultural resentment aimed at liberal institutions perceived as hypocritical or elitist.

While these gains among Black men do not fundamentally alter the story of Trump’s core appeal, built on revanchism and racial hierarchy, they provide just enough top cover for mainstream media and pundits to frame them as evidence of ideological diversity within the MAGA movement. This cynical framing obscures the deeper truth: that fragmented solidarity within Black America leaves many more vulnerable to exploitation, manipulation, and political alienation.

Privatized Repression: The Politics of Public Death

Public education in America remains mired in racial hierarchy due to its localized nature and its potential to cultivate multiracial spaces where children can evolve past learned hatreds and stereotypes. Following the Civil War, Radical Republicans in Congress pushed for public education in the South to benefit both former slaves and poor Whites. This effort was met with fierce resistance because education threatened the social order that kept a few powerful interests in control. As Reconstruction efforts waned, Southern oligarchs exploited racial division and fear, persuading people to support leaders who appealed to their prejudices but offered little in the way of rights, democracy, or social safety.

While much of the Black population remained concentrated in the American South, the Great Migration would soon spread Black labor across the nation, as people fled state-sponsored terrorism and sought economic opportunities elsewhere. This demographic shift meant that desegregation, while rooted in the South, eventually became a nationwide battle.

Efforts to expedite integration across America were met with stiff resistance. Following the initial shock of mob resistance to school integration in the mid-20th century, White Americans mobilized through dollars rather than violence. They fled school districts growing more multiracial, moving to suburbs or sending their children to private schools. Though schools and neighborhoods weren’t completely White, the successful integration of minorities was often the exception, not the norm.

Meanwhile, in predominantly Black, working-class neighborhoods, systemic degradation continued at a rapid pace. Some Black and non-Black leaders have tried to support majority-minority environments by remaining in cities, contributing to the tax base, sending their children to local schools (even while shielding them from the worst excesses of these environments), and participating in community pillars like churches, farmers markets, health fairs, and grassroots organizations.

Still, these efforts are insufficient to save public resources that are growing scarcer as essential services are increasingly outsourced to the private sector—an enduring legacy of the marriage between privatization and backlash against racial integration. This “public death” is most visible in the decrepit state of America’s once-great cities, now defunded spaces plagued by crime, addiction, and cycles of deprivation as resources are inequitably distributed and tax bases continue to erode. It’s essentially “drained pool” politics but on a much larger scale.

Choice and Consequence: The Charter School Divide

The survival-first mindset of working-class Black Americans, living in predominantly Black and underfunded spaces, has increasingly diverged from the solutions championed by a Black elite still operating within the framework laid out by Du Bois’ Talented Tenth and the early leaders of the National Civil Rights Movement. Nowhere is this divergence more apparent than in the fight over charter schools in Black communities.

Polling consistently shows that Black support for charter schools continues to increase despite pro-public education advocates presenting data-driven evidence showing how charter schools divert resources from public schools. By attracting the highest-performing students, charter schools leave public institutions saddled with the costs of high-need students. This dynamic makes public school operating budgets unsustainable as their ability to compete diminishes.

Yet charter school advocates boast of higher performance ratings, stable environments, and the support of engaged parents. The American Federation of Children, a pro-school choice organization, reported that as of 2024, 73% of Black voters polled supported school choice—higher than White (71%), Hispanic (71%), and Asian (70%) voters. Similarly, Education Next found that two-thirds or more Black and Latino Americans favored charter schools and vouchers, often outpacing White support. Notably, those of modest means were more likely to support vouchers marketed as helping poorer students, while higher-income individuals showed less enthusiasm, potentially due to their own access to more options.

However, these numbers don’t suggest that Black Americans are abandoning public education altogether. A 2023 poll by Democrats for Education Reform found that 67% of Black voters supported public charter schools, but an identical 67% preferred public school choice over private school vouchers. The trend reflects a desire for viable alternatives to a public school system that consistently underserves Black communities.

Nowhere is this conflict more apparent than in Maryland, where the Old Line State features one of former Governor Larry Hogan’s legacies, the BOOST program. This voucher-like initiative is marketed as a benefit to disadvantaged, often minority, communities. However, opponents argue that it diverts critical funding from public schools, creating an unjust parallel system financed by public money. The Maryland State Education Association (MSEA) reported that nearly 70% of taxpayer dollars allocated through the BOOST program were distributed to families whose children were already enrolled in private schools. Still, statewide polling shows 74% of Marylanders support the “freedom to choose the best educational setting for their children,” with 84% of Black Marylanders expressing support.

At least Maryland’s charter system maintains some semblances of public accountability, as state law requires charter schools to remain under the authority of local boards of education. Former Governor Hogan proposed loosening these standards, but educators successfully rebuked the attempt, citing the lack of strong oversight in other states like Louisiana. This distinction highlights how Maryland’s model, while flawed, at least acknowledges the importance of maintaining some level of public control over charter operations.

The situation is far more extreme in Louisiana, particularly New Orleans, where charter schools have become the norm. After Hurricane Katrina, the state took control of almost all New Orleans’ public schools and converted them into charters, closing neighborhood schools without community input. The firing of 7,000 public school employees—4,000 of them Black women with an average of 15 years of experience—eroded a critical Black middle-class workforce and damaged social trust.

The NAACP, often seen as a Black elite institution, joined others in condemning New Orleans’ charterization model, where 29 different organizations operate 68 schools with unelected boards. Scholars have called this policy shift a “man-made disaster” that alienated the community by implementing reforms to Black communities rather than with them.

Despite these democratic and operational concerns, the popularity of charter schools cannot be ignored. Public education advocates argue that promoting “funds following the child” sounds good but “seriously reduces public school services” and creates a “duplicate system that duplicates services and costs.” This argument seeks to reframe the narrative from “individual choice” to “collective progress.” But it increasingly falls on deaf ears as desperation grows in communities that feel trapped within a broken public education system.

Betrayal of the Dream

In the past, I have leaned toward the position of pro-public school advocates. Education is the bedrock of a democratic society, providing the lifeblood for change by fostering dynamic, diverse spaces with children of all racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and religious backgrounds. But that belief belongs to an ideal America.

The reality of American life, particularly after Donald Trump’s second-term victory despite his violence and crimes, is that our democracy has cratered under the weight of oligarchical backlash. Racially coded political campaigns have driven the nation toward a privatized dystopia that resembles the Gilded Age’s robber baron era, only retrofitted for the internet age.

As I wrestle with my assumptions, I’m forced to question whether Black America can be saved through the frameworks of the 20th century. Black America has never endured this type of fragmentation of lived experiences: one segment thrives in a new economy of finance, education, and information systems, while another languishes in deindustrialized sectors, de facto segregation, and a belief that Black leaders are selling them out despite their well-meaning rhetoric.

Given the widening gap between Black elites and the working class, I find myself reconsidering Booker T. Washington’s emphasis on practical skill-building and economic resilience, though not the excessive intragroup nationalism that some of his ideological successors have embraced. America has proven itself a system addicted to systemic oppression and cultural pathologies that have devastated Black Americans from one generation to the next. Perhaps instead of trying to reform a fundamentally anti-Black system, a new framework focused on intra-Black uplift is necessary—a framework resilient enough to survive a nation determined to deny our progress.

On a personal level, I grew up in a dangerous city where attending my local public school was never an option. My parents had to filter me into environments they trusted, shielding me from becoming another statistic. As a Black male living in a predominantly Black urban community, I grew up under the shadow of white backlash’s destruction—a reality where survival itself feels precarious. Any misstep—a friend I made, a wrong turn I took, a casual relationship—could spiral into something far darker. I know people serving prison sentences simply for associating with someone who was unknowingly harboring a murder weapon. I know people shot dead in their cars in front of their homes, mistaken identities ending lives in an instant.

This is the America I inherited: an America that preaches post-racial democracy in affluent and diverse spaces but ruthlessly enforces de facto segregation when I return to communities still shedding the legacies of this country’s darkest chapters. As someone who obtained higher education and learned a professional trade suited for the information age, I’m acutely aware of the widening gap between myself and others in my community. My framework for change and survival differs from those who cannot afford the luxury of contemplating systemic reform and instead search for any immediate opportunity that offers stability.

Some find that opportunity by clinging to the ideals of historical solidarity. Others, however, accept the grim reality of a post-white backlash world, even if it means embracing frameworks that undermine the legacy of our ancestors. And history is making something painfully clear: our predecessors fought a noble battle against a profoundly racist nation but ultimately lost. Their efforts, while remarkable, cultivated a wave of anger and insidiousness among those who opposed racial progress—a rage that now fuels America’s spectacular decline from superpower status. The tragedy is not just the violence inflicted upon us but the ways we have been maneuvered into fighting each other.

Things were rolling along pretty smooth, until the Vietnam war and demand for social justice, brought the sons and daughters of the well to do middle class, something unheard of in history, to the streets.

The rebellion worried and upset the established order. The result was thata lawyer for the tobacco institute, and member of the Heritage Society, named Lewis F Powell Jr https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewis_F._Powell_Jr., wrote a memo to his friend and neighbor Eugene B. Syndorn President of the Chamber of Commerce, that the problem was that there was a middle class, too well off, that they could send their children to college, were they were indolent, had no appreciation of the capitalism that gave them leisure, and that the middle class needed to tighten there belts. Months later Richad Nixon appointed him to the Supreme Court

The Memo that Hijacked American Democracy: https://hartmannreport.com/p/the-memo-that-hijacked-american-democracy-b4f

It was all downhill from there, Starting with Nixon there has been a concerted attack to neuter the middle class. Paul Volcker, then Chairman of the Federal Reserve said in 1974, that he saw it as his task to reduce the standard of living of the middle class, ostensibly to reign in inflation, but we know better.

10 years later the central bank of central banks, the Bank for International Settlements in Basel,Switzerland said the same thing but in regard to the free world.

And today, if you sweep aside all of the b.s., what you see is the extension of that idea, and the tool is dividing the people against themselves,

We the idiots, have no idea, that we are all in the same boat, and that boat is sinking.