Why Does it Feel Like America is Naive?

American naiveté, ICE, standing armies, and James Madison.

If we actually think about this for a second, then perhaps America performing an act of self-disembowelment upon itself in front of an audience or at least showing its uncommitment to democracy, which was understood by most marginalized populations, isn’t entirely unexpected if we flick our finger and let go of our American Exceptionalism enchantment.

With its legacy as a global power in an era characterized by lethal, global totality in mechanized warfare, America still had not come to terms with its own contradictions regarding its stances on liberty and had left itself prey to a narrative fiction in which its sacrifices in the Civil War era constituted but a half-reckoning. The emancipation of chattel slavery served as an excuse for its long afterlife as a means of coercion, Black codes, debt peons, convict leasing, and sharecropping. All of these instincts made freedom contractual and local.

Thus, it can be argued that this nation was more of a “trust fund baby” that lived through history’s lottery, as the colonial aspirations of the Global North and two World Wars ravaged the economies surrounding it. However, this “trust fund baby” named America never really understood how it got its riches, which makes it all too likely to squander it, especially after it begins to think that its bank balance equates to virtue.

Of course, there have always been fears about American power, at least as seen from outside the country, at least as long as the country itself has existed, and not merely the “well, the Europeans are jealous” variety that Americans like to think to get a good night’s sleep. Britain’s own George Canning, writing in the 1820s, essentially brags that he “called the New World into existence to redress the balance of the Old.” That is, he admits that the New World already figured into the politics of the Old, and that the idea of a New World at all was already a factor in the rivalry between the old powers.

Alexis de Tocqueville, writing in the 1830s, makes the more disquieting observation: the Americans and the Russians, he says, are the two emerging giants, and the American approach to conquest passes through “freedom,” while the Russian approach passes through “servitude.” Don’t be fooled by the rhetoric of freedom and think that freedom implies the absence of control. Control can be the technology.

And then, of course, you have the European whiplash of the 1860s. So, during the Civil War, or during the period of the “republic” as it’s trying not to die, France decides to move into Mexico, sets up Maximilian, and tests how distracted it can make the United States. And after the Civil War, it’s clear, particularly through Secretary of State William Seward’s diplomatic efforts, that the United States will not view the attempt at a European-sponsored monarchy as an “aw, ain’t it sweet” kind of thing, but as an actual threat to what it considers to be its prerogative. Or, as it turns out, the empire has had its nervous breakdown, but it’s still an empire.

The end of the 19th century finds Britain no longer viewing the US as a loud relative at a family reunion, but rather as an industrial monster building a base of resources, railroads, finance, and population. It’s essentially a flywheel for geopolitics.

And at the start of the next century, the old worries are back, but this time not so much a matter of “Will America be strong?” but rather “What are the implications for the world order when a superpower acts like a provincial teenager with a credit card?”

America may be young, like the 25-year-old hedge fund manager, the kind of young that, while not quite the equivalent of the hormone-addled teenager, still thinks it can use the logic it developed at the University of Vermont to control the nuclear arsenal. Oscar Wilde may not have said it, but the notion that America skips directly from barbarism to decadence without ever passing through civilization has the kind of staying power that makes it seem like it was said by Oscar himself.

G.K. Chesterton, visiting in the early 1920s, describes how “young nation” was wielded like a magic wand, making everything clear and excusable. “Oklahoma was proud of having no history—A great future—and nothing else!” And then he basically says that this country’s got a sleeping giant that’s just waiting to be awakened, where politics can be used to squelch dissent through sheer unanimity. The thing about that isn’t that American people are inherently awful. It’s that American society was still trying to develop a civic religion while possessing continental-scale leverage.

André Siegfried (writing for The Atlantic in 1928, after repeat visits) captures the European mood perfectly: immense capacity plus juvenile spirit. He describes the impression of America as “eccentric, erratic… already colossally rich,” and contrasts the older, memory-heavy parts of the U.S. (his example is Richmond, where people carry lineage and inherited culture) with a newer America centered on production, efficiency, and self-satisfaction. An America that can imagine the outer world disappearing and still think it would “continue to prosper.” That’s the adolescent empire in one sentence: a civilization whose confidence is so total it starts mistaking insulation for wisdom.

Then, because, as is often pointed out, history loves a callback, you get Charles de Gaulle in the 1960s, looking at an American-led alliance and saying: we get that you’re helping us, but we’re not going to live inside your machinery. The letter clearly addresses issues of sovereignty and command structure, as well as scale. The US role in global affairs is massive, to the point that its own allies treat it as something that needs to be worked around.

But, I ask you, does having a long history make societies humble? Sometimes. Usually, it simply makes them more sophisticated in their hypocrisy. Old empires know how to live with contradiction: they establish archives, procedures, nomenclature, and cadres of professionals fluent in speaking of extraction as stability, of repression as order, and of privilege as tradition. If you seek to have your society be humble, you do not merely need it to be old. You also need it to be accountable, to have lost, and to have a politics that actually retains a memory. Which is why the view of America as a young nation making old mistakes is a line that hits. Because the US was given the inheritance of world-historical power and yet was unable to work through the fundamental contradictions of its own history of racial domination, conquest of native people, exploitation of workers, etc. When your narrative of self is “we are freedom,” you can see every criticism of you as treason and every restriction of you as oppression. That’s the fragility of a superpower, not because it doesn’t have power, but because it can’t face reality.

And, of course, if you’d like the present tense punchline: well, the reason is, it’s not that America’s changed, exactly. It’s that an increasing number of Americans, at home and abroad, don’t feel obligated to feign surprise when the mask slips, so to speak. Various indices of democracy and various civic freedom monitors have been tracking this phenomenon for some time now, and the past couple of years have simply amplified it to the point where we can speak of ‘theater’ rather than ‘erosion’. We’re seeing courtroom battles over executive authority, we’re seeing civic space constricting, we’re seeing mass demonstrations that don’t so much feel like “policy disagreement” as “legitimacy crisis”.

Thus, yes, the Brits and French have a lot to say. Not because they are saints (lol), but because older empires have a tendency to see one of their own in a rising empire that speaks in idealistic terms but acts like a very particular machine. The only question, of course, is whether we’ll learn from that example before we have to pay the usual tuition of humiliation, decline, and rebuilding a civil culture that doesn’t need mythology to work.

References:

Canning, George. Speech in the House of Commons, December 12, 1826 (quoted in Hansard Parliamentary Debates).

Chesterton, G. K. What I Saw in America. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1922.

Siegfried, André. “The Gulf Between.” The Atlantic Monthly, March 1928.

Tocqueville, Alexis de. Democracy in America. Translated by Henry Reeve. New York: J. & H.G. Langley, 1841.

United States Department of State. Papers Relating to Foreign Affairs, Part III (1865 materials). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1866. (Includes William H. Seward letter to John Bigelow.)

United States Department of State. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume XIII: Western Europe Region. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1995. (Includes Charles de Gaulle letter to Lyndon B. Johnson, March 7, 1966.)

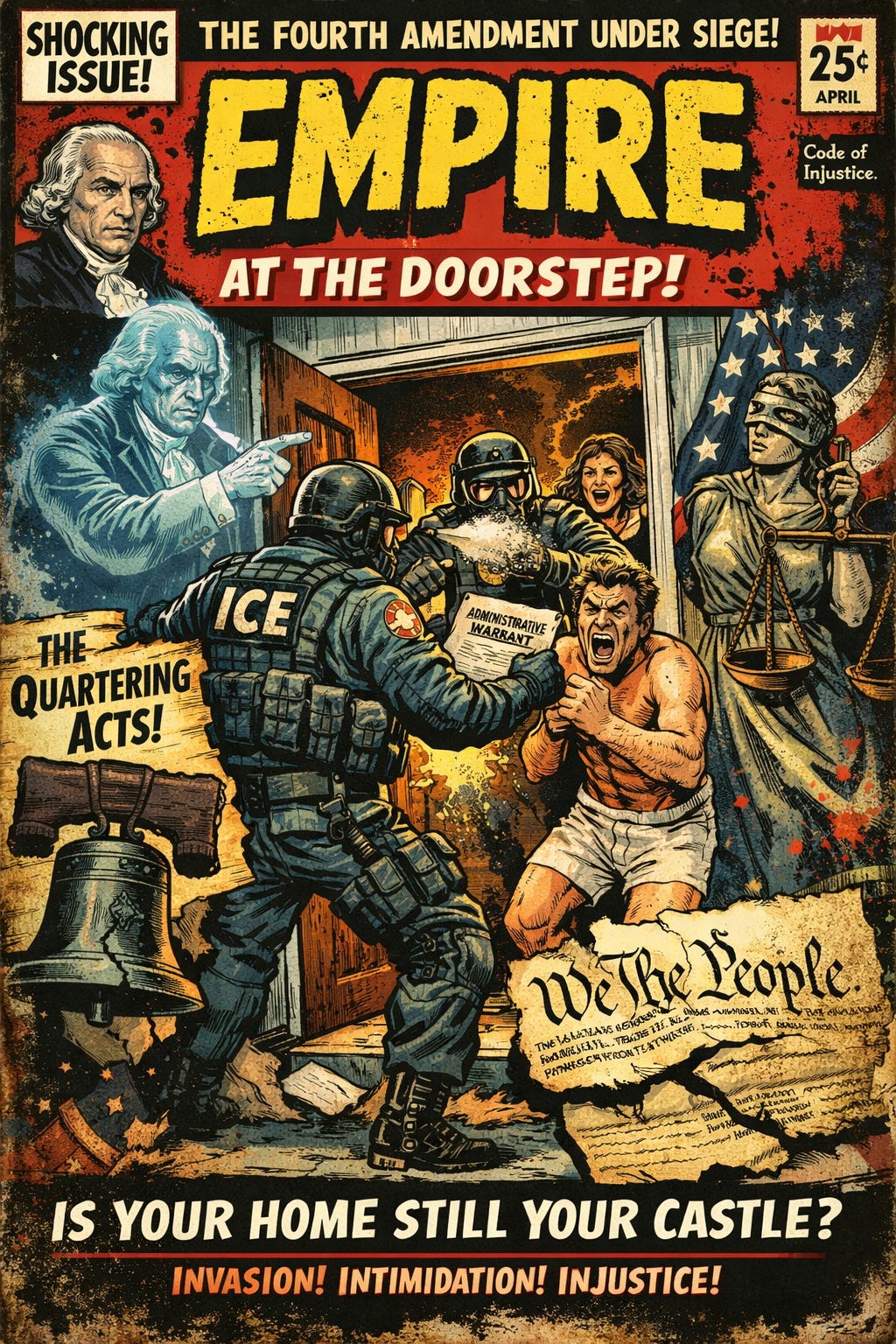

On ICE and Standing Armies

There is a lot going on with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and a great deal of attention should be focused on the issue. In Minnesota, a federal appeals court intervened and lifted the restraints a federal district judge had put in place to try to curb the actions of ICE to prevent violence and retaliatory actions against protesters. In plain terms, the government can just keep on keeping on with what they are currently doing, which includes pepper-spraying protesters in Minneapolis.

Meanwhile, the Associated Press reported that ICE has said it can enter a home under an administrative warrant, which is essentially a piece of paper issued by the executive branch without a judge’s signature. That’s not a minor distinction. It’s the difference between a state that is limited by an independent court and a state that validates itself. It doesn’t make a home a space that replaces permission with procedure.