Author’s Note: I’ll have another newsletter out on Friday, and then again on Monday and Tuesday of next week. As the year winds down and the holidays set in, I hope you’re finding small ways to rest, reset, and stay grounded in what actually matters.

We’re also very close to a milestone here: 17 paid subscribers away from reaching 100. I’m running a holiday discount that gives you 30% off a full year of Stew On This, that’s $35 for the year, or $3.50 a month.

If this work has been valuable to you, if you care about independent media, historical context, and analysis that tries to slow the noise down rather than add to it, I’d be grateful if you considered subscribing and helping us cross the line.

Either way, thank you for being here and reading.

CBS News has a proud history, but like all histories, it carries its share of messiness and letdowns. 60 Minutes in particular represents the high-water mark of the television news era. It included long-form reporting designed to slow the viewer down, confront power directly, and ask audiences to sit with uncomfortable truths rather than scroll past them.

For decades, 60 Minutes earned its reputation through adversarial journalism that did not depend on official cooperation. Mike Wallace’s confrontations with tobacco executives, General Motors, and other corporate titans were built on the premise that power did not get veto rights over exposure. Dan Rather’s early reporting and Steve Kroft’s deep dives into political corruption, including Iran-Contra, unfolded amid institutional resistance and outright stonewalling from those in charge. Andy Rooney’s closers worked precisely because they assumed a shared civic space where facts still mattered.

Morley Safer’s Vietnam reporting remains the clearest example of that ethic. His coverage did not wait for Pentagon approval or White House buy-in. Instead, it forced Americans to confront the human cost of an imperial war and the gap between official narratives and lived reality. That kind of journalism did not flatter authority.

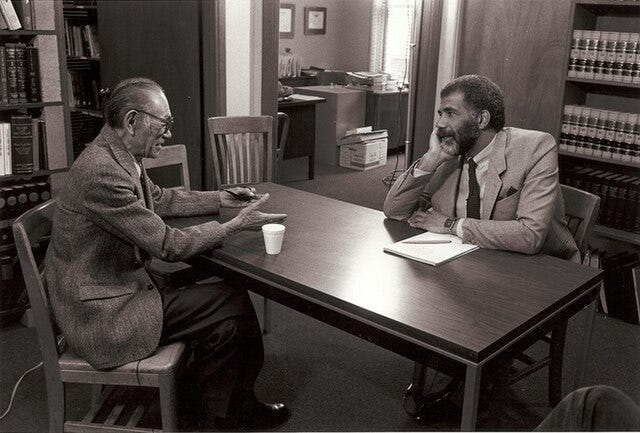

That same spirit is captured in the image at the top of this piece: Fred Korematsu sitting across from Ed Bradley. Korematsu was a historical curiosity, and he was living proof that the American state can act unanimously and still be profoundly wrong. He was an American citizen imprisoned for his ancestry, upheld by the Supreme Court, and vindicated only decades later, and his story is a reminder that legality and morality often diverge. Ed Bradley understood that, as one of the defining figures in 60 Minutes’ history, so he wasn’t interested in balancing injustice against official explanations. He was interested in the memory of what the country did, why it did it, and what it took so long to admit. That interview existed because 60 Minutes once believed that silence, denial, and discomfort weren’t reasons to move on, but reasons to stay with the story longer.

That legacy is something Americans should be proud of, and it’s why the present moment is so painful to watch. When a news package must secure consent from a White House that either recycles debunked talking points or communicates through strategic silence, journalism ceases to function as an interrogation of power and becomes an exercise in risk management. The absence of official cooperation was once the reason to report, as in the age of Trump and media consolidation, it increasingly becomes the reason not to.

This shift reflects a broader degradation of journalism as a field, a practice, and a democratic institution. Editorial caution has hardened into self-censorship, driven by access journalism, brand protection, political retaliation, and the logic of corporate media ownership. Looking back, I suspect we will see the rise of explicitly disinformational outlets, Fox News chief among them, not simply as partisan actors, but as accelerants that lowered the standards for the entire ecosystem.

What has been lost is not perfection, but a shared expectation: that journalism exists to challenge power even when doing so is inconvenient, uncomfortable, or costly. Once that expectation erodes, it is not just a show or a network that changes, but the once-emerging democratic culture that depends on it.

What the Epstein Files Actually Reveal

Let me start with what this is not, because clarity matters more than heat right now.

The Epstein file release that just happened does not incriminate the current president, Donald Trump. That much should be made clear. Being mentioned in investigatory documents, especially ones this sprawling and this old, is not the same thing as being charged, let alone proven guilty. Pretending otherwise doesn’t strengthen accountability. It cheapens it.

But saying that doesn’t mean there’s nothing here. It just means the story isn’t where many people want it to be.

What these files do add is suspicion, and that is not toward a single figure, but toward the internal machinery of the United States Department of Justice itself. And once you see it that way, the unease settles in your chest and doesn’t really leave.

Because what’s being exposed isn’t a lack of investigation. It’s a lack of resolution.

We Can See the Work. We Can’t See the End.

The Washington Post reporting shows prosecutors doing exactly what we’re told the system is designed to do. Subpoenas are issued, and records are requested while internal emails are exchanged. Then flight logs are reviewed, added by tips, some credible, some obviously not, that are logged, preserved, and contextualized.

This is what institutional seriousness looks like on paper. Gears turn as files grow, and the bureaucracy hums along.

And then Politico quietly pulls the camera back and asks the more unsettling question: what happened to all of it?

Tens of thousands of documents appear on a Justice Department URL. They remain available for hours. Then they vanish. No explanation. No acknowledgment. Just silence.

We’re told there are memos, specifically, seven pages on possible co-conspirators, an 86-page update on prosecutorial strategy, additional analyses on corporate liability, and other potential targets. We’re told that after Jeffrey Epstein died in federal custody, prosecutors seriously considered how far the case might still go.

But we never see those deliberations carried through to a public conclusion.

The gap between investigation and accountability, or the space where decisions are made and never fully explained, is where trust goes to die.