Author’s Note: Sorry for the late newsletter today, folks. It has been a pleasant Giving Tuesday. In the spirit of giving, please keep an eye out for your favorite campaigns and causes, which are likely asking for a little bit of help today. As always, if you are in the giving spirit and find value in this work, then consider becoming a paid subscriber to Stew On This.

Miguel Tinker Salas’s Staying the Course: United States Oil Companies in Venezuela, 1945–1958 explores a pivotal era in Venezuelan history. One often mythologized as a break from dictatorship and a leap toward democracy. Yet as Salas shows, oil remained the ruling language. Even as Rómulo Betancourt and the Acción Democrática party rode the wave of the 1945 October Revolution, foreign oil giants like Creole (Standard Oil of New Jersey), Shell, and Mene Grande (Gulf) had adapted, co-opted, and stayed in control.

Their strategy wasn’t confrontation, but a calibrated compromise, or a soft imperialism by contract and concession. They offered mild labor reforms, allowed modest tax increases, and aligned themselves with whichever government would guarantee “stability,” whether that was a democratically elected coalition or a military dictatorship. In other words, they didn’t care who ran Venezuela, as long as the oil kept flowing.

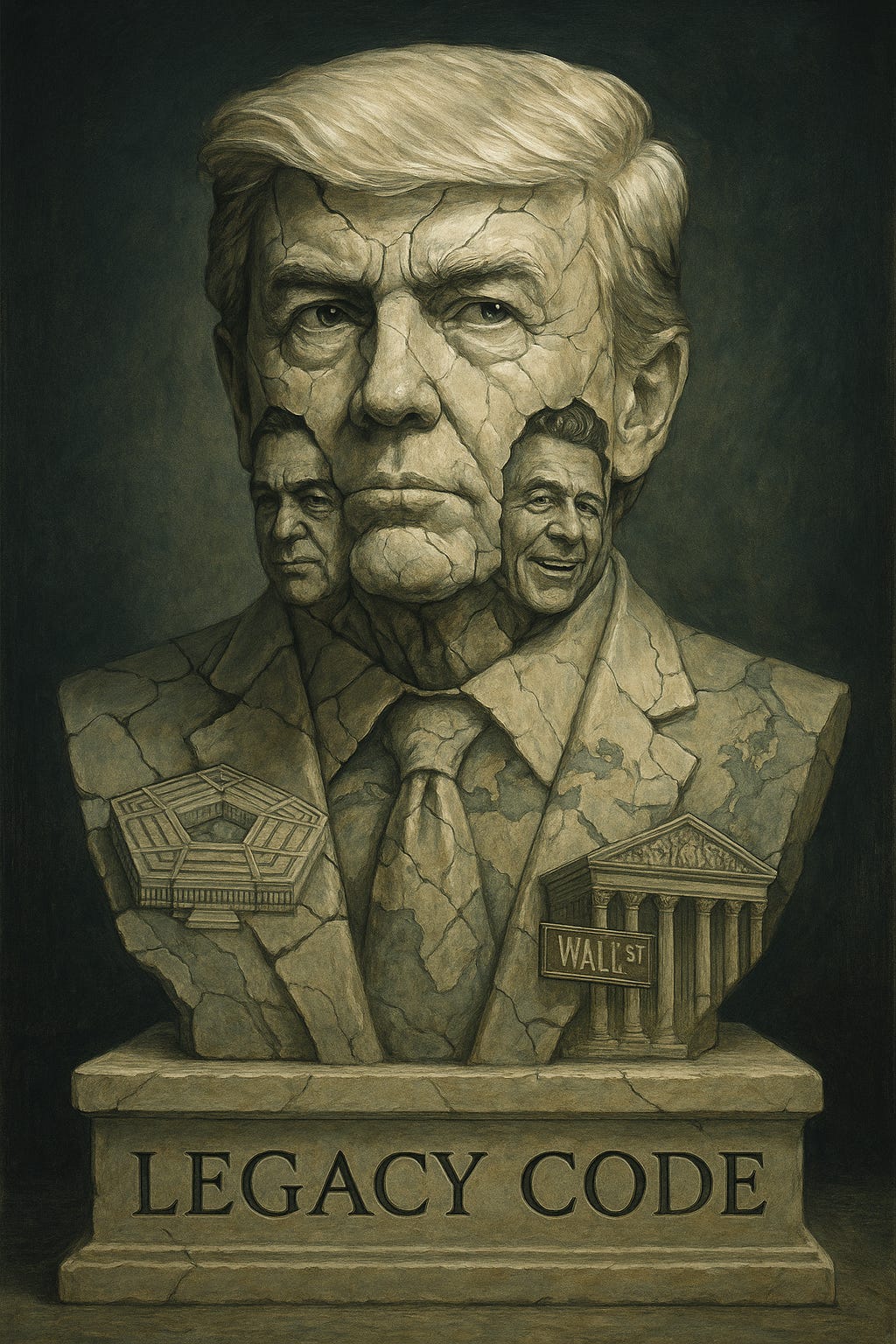

This is not just dusty history. It is a prelude.

Today, as human rights abuses mount and migration surges, oil profiteering remains a life-or-death game, not just for Venezuela, but for the geopolitical chessboard it sits on. And the recent moves by the Trump administration, including militarized threats and ambiguous airspace decrees, are not aberrations. They’re the mask-off version of a much older playbook.

Where Creole once negotiated behind closed doors, Trump now brandishes missiles on Truth Social. Where the U.S. once backed dictators quietly, now it flirts with naval escalation in plain view. The friendly façade has fallen away, but the objective remains: leverage Venezuela’s instability for U.S. strategic and economic gain.

Even the post-1999 Bolivarian era, marked by Hugo Chávez’s nationalization of oil and the rhetorical break from Washington, fits the pattern. When direct control over resources slipped, U.S. tactics shifted: from backroom deals to sanctions, from policy pressure to regime-change flirtations. Now we get a collapsing state, a humanitarian exodus, and a political vacuum now filled with narcoterror rhetoric and border militarism.

To call Trump’s recent actions “unprecedented” is not just lazy, but historically dishonest. He is not a rupture, but a continuation: the Nixonian madman theory in the age of memes, playing out the same imperial dynamics with less restraint and more spectacle.

The U.S.–Venezuela relationship has long been dictated by the logic of oil first, people second, whether under Betancourt, Pérez Jiménez, Chávez, or Nicholas Maduro. And in this story, the people of Venezuela, whether demonized migrants or disposable labor, are rarely given the space to narrate their own future.

There may be a Trump Derangement Syndrome problem.

Spencer Ackerman wrote a searing piece about the now-slow-dripping horrors of the boat strikes in the Caribbean. I highly suggest you read it. It not only parses out what’s new in this moment, namely, a direct order to murder survivors, but places it in the context of decades of special forces impunity and imperial muscle memory.

His piece got me thinking about Trump Derangement Syndrome, not the MAGA-fied insult tossed at liberals on cable news, but the quieter, more insidious form found in donor-fed media and institutional op-ed land. It’s the kind that insists every grotesque development in Trump’s America is a deviation from some imagined moral high ground, rather than the logical, maskless evolution of a system already cracking its knuckles.

Trump didn’t just fall out of the sky like a lightning bolt. He was forged in the backlash to civil rights, in the bipartisan romance with market fundamentalism, in the smoldering ruins of a post-Cold War consensus that replaced material progress with PR and vibes. He rose out of a landscape where inequality widened, social trust eroded, and the only consistent ideology was protecting capital. That consensus still calls itself the “center,” even as the country burns from the edges inward.