The White House has published an official government website stating that the January 6 rioters were peaceful, and that the real insurrection was the certification of electors following what officials describe as a stolen election. The audacity of this moment should be unsettling regardless of partisan alignment. More troubling still is that it was predictable. Once the 2024 election was lost, there was a ticking clock on when history itself would be formally rewritten by one of the most powerful political institutions in the world.

This should not be understood as routine messaging or political spin. It is better described as state-sponsored memory production or the use of official platforms to fix a contested narrative into the public record. When governments do this, the objective is rarely to persuade critics. It is to legitimate supporters, marginalize dissent, and convert interpretation into orthodoxy. At that point, disagreement ceases to be a civic act and becomes deviance.

This pattern is not unique to the United States, nor is it tied to a single ideology. Throughout history, governments facing legitimacy crises often respond by reshaping the past. The mechanism is familiar, including selective curation of facts, the inversion of moral responsibility, and the elevation of one version of events through institutional authority. The danger lies not in propaganda itself (every political system produces it), but in the moment when official institutions decide that narrative stability matters more than factual dispute.

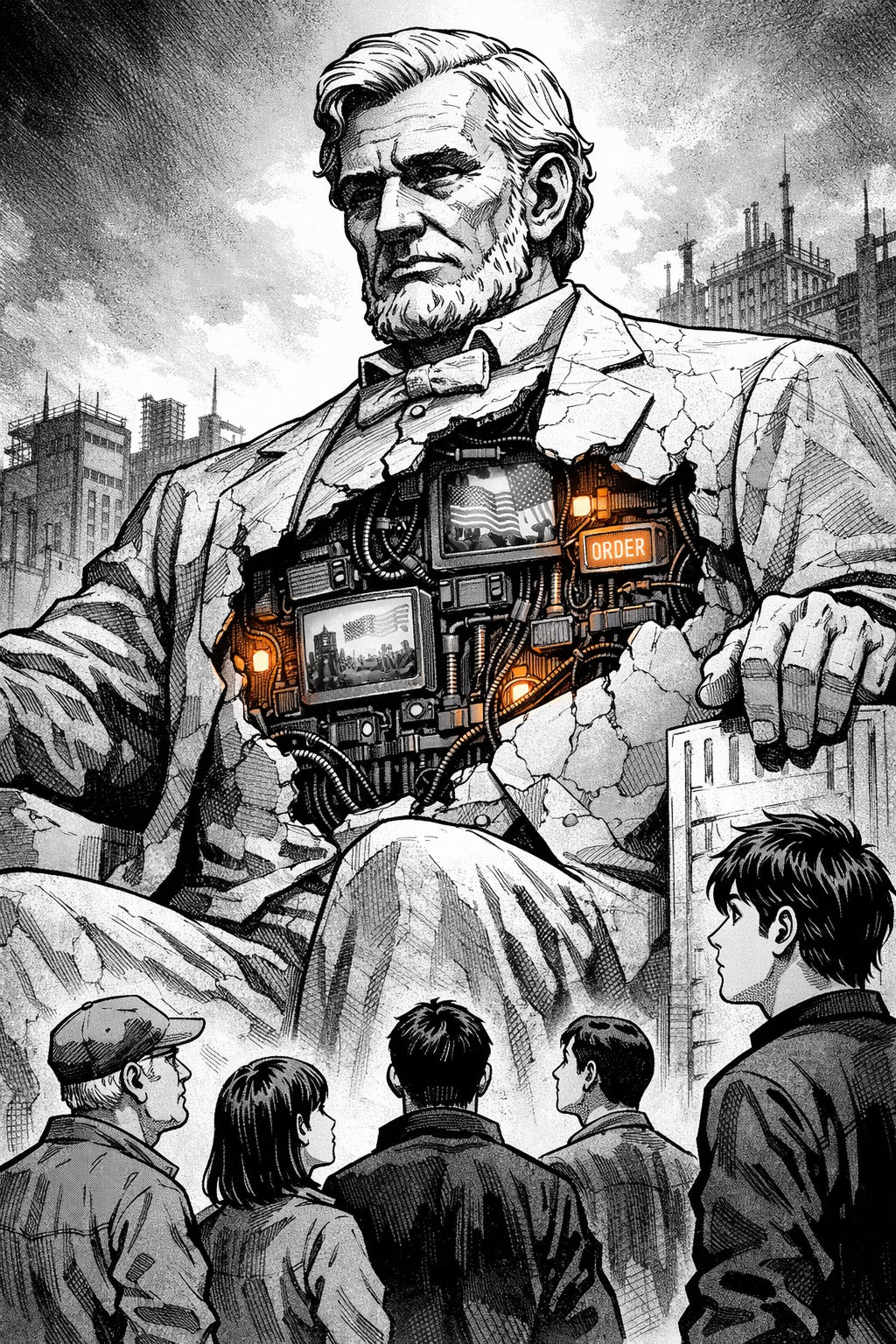

Americans, in particular, should resist the temptation to view this as unprecedented or foreign. The country has engaged in similar acts of historical revision before. After the Civil War, the United States spent decades constructing a narrative that minimized slavery, reframed secession as honorable dissent, and pushed Black Americans to the margins of the national story. This revision did not emerge solely from extremist corners. It was embedded in textbooks, memorials, and public institutions. Over time, omission hardened into memory.

Notably, this period of historical distortion coexisted with real progress. The nation industrialized, expanded democratic participation for some, and asserted itself globally. But the cost of unresolved historical truth was deferred rather than avoided. The myths embedded in official memory shaped political incentives and social conflict long after the original generation had passed. The lesson is not that revisionism immediately collapses democracies, but that it quietly alters the conditions under which future crises are resolved.

That lesson applies directly to the present. The United States now operates in an environment of extreme polarization and fragmented media, where institutional trust is already low, and grievance narratives are highly profitable. Over the past several years, major national crises, including a pandemic and a violent breach of the Capitol, were filtered through partisan lenses almost immediately rather than treated as shared civic emergencies. The result is a public that does not merely disagree on policy, but on the basic description of reality.

Within this environment, belief has taken on a new function. Acceptance of certain claims about January 6 or the 2020 election is no longer just an opinion; it is a signal of group membership. Publishing an official government website that affirms one side of this epistemic divide does ot resolve the dispute but instead institutionalizes it. What was once a partisan interpretation is elevated to state-backed history.

This escalation is occurring alongside the other destabilizing development of individuals who participated in or were connected to the events of January 6 receiving pardons and political validation from the highest office in the country. Whatever one’s view of those decisions, the effect is to blur the boundary between accountability and allegiance. In systems already strained by mistrust, that ambiguity matters.

The deeper concern is not January 6 as a discrete event, but the precedent being set. The United States will face future transfers of power amid demographic change, economic pressure, and sophisticated disinformation ecosystems. The critical question is whether institutions tasked with recording and interpreting events will act as referees or as participants.

Seen this way, official historical rewrites are not symbolic excesses. They are early indicators. History suggests that when governments resolve disputes about reality through authority rather than evidence, the damage is rarely immediate but often enduring. Once institutions choose narrative closure over open inquiry, truth becomes contingent on power.

This raises a final question that transcends party politics. American influence has long rested not only on military or economic strength, but on credibility, the belief that its institutions (while imperfect) remain anchored to observable reality. When that anchor weakens, soft power erodes, and coercion fills the gap. Democracies that make this shift rarely do so deliberately, and they rarely reverse it easily.

The issue, then, is not whether one agrees with this administration or distrusts the opposition. It is whether Americans are willing to accept a future in which history itself becomes a tool of governance rather than a record to be argued over in good faith. That choice, once made, tends to outlast any single election.

The Erosion of America’s Soft Power

This cascade of events, involving America’s renewed flirtation with expansionist instincts to the official rewriting of January 6, raises a deeper question about the durability of American soft power, particularly as it relates to the survivability of democratic norms beyond our borders.

For much of the postwar era, the United States exercised influence not because it was free of contradiction, but because it appeared willing, however unevenly, to confront them. The American story remained compelling precisely because it was unfinished. Despite profound hypocrisy, including the persistent afterlife of white supremacy often minimized by both center-left and center-right institutions, the country projected an image of a society capable of self-correction. Political freedom, dissent, and pluralism were framed not as gifts bestowed from above, but as hard-won outcomes of generational struggle by Americans of all backgrounds.

That struggle formed the moral core of American soft power. Many Americans took Lincoln’s description of the nation as the world’s “last best hope” seriously, particularly as despotism expanded across regions beyond U.S. influence. Diplomats, aid workers, soldiers, and civil society actors engaged abroad, believing sometimes earnestly, and sometimes naively, that democratic norms could be encouraged through persuasion rather than imposed through force.

A paid subscription gets you:

Full access to the archives

The ability to comment and join the conversation

Stew’d Over, and other bonus daily newsletters!

Live Ask Me Anything sessions with paid readers

This independent work is sustained by readers who want more than headlines and hot takes.