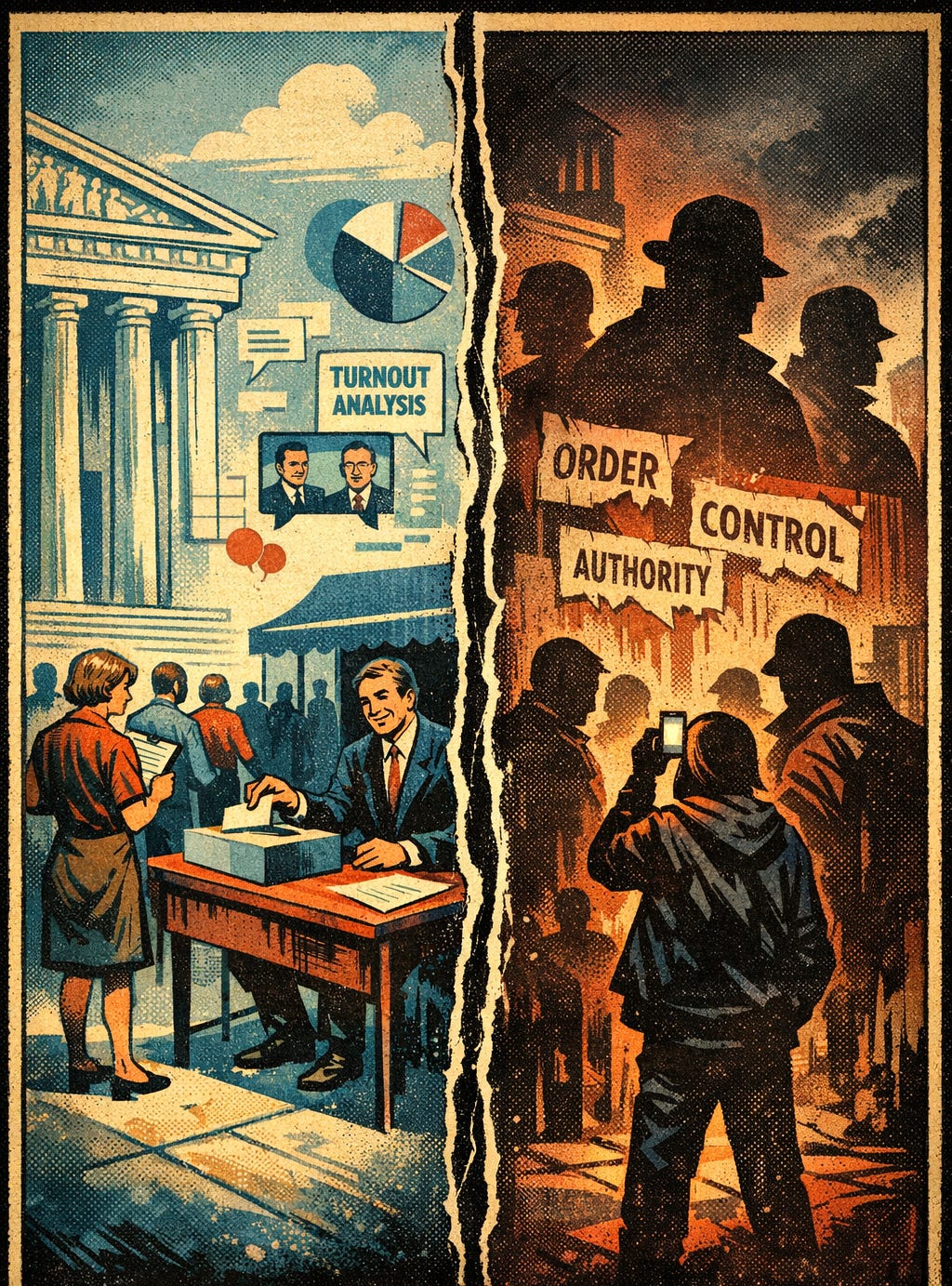

The next several essays will live at the fault line where “the nation” ends and “the states” begin because that seam is where American democracy both breathes and bleeds.

As ICE has expanded into a truly nationwide footprint, the question isn’t only what federal power can do. It’s what kind of civic terrain it lands on. In one state, a raid meets a thick web of journalists, clergy, mutual aid networks, lawyers, city officials, county attorneys, and neighbors who know exactly which phone tree to light up. In another, the same action hits a thinner civil society, friendlier local authority, and a citizenry trained by history and habit to treat the state like an electrified fence: touch it, and you learn pain.

Which brings me to V.O. Key because Key’s work is basically the field guide to how “states’ rights” becomes a machine. In Alexander Lamis and Nathan Goldman’s essay on Key’s collaboration with Alexander Heard and the research orbit around Southern Politics, you can feel the system humming: officials performing racial demagoguery as daily governance, public incompetence treated as a feature, not a bug, and an entrenched business/planter elite harvesting power from fractured labor solidarity and enforced social codes. The South that V.O. Key documents didn’t merely represent conservatism, but a one-party order. A political ecology designed to centralize real authority upward to local oligarchs while exporting the costs downward to everyone else.

And that’s the through-line into 2026. Thankfully, we now have the public vocabulary to name what Key was mapping with the tools of racialized rule, institutional capture, civic intimidation, and the way local control can be a velvet glove over a closed fist. But the late 1940s aren’t ancient history. They’re still vanishingly close to living memory’s penumbra, and the habits of governance Key described had migrated, rebranded, and sometimes been digitized.

The deeper question I’m chasing in this series is, does the backlash we’ve seen in places like the Upper Midwest and the West Coast travel well? Or does it collapse when it enters jurisdictions where local power is more ICE-friendly, where discrimination is kept out of plain sight (clean paperwork, quiet cooperation), and where fear of reprisal is a civic norm rather than a scandal?

In other words, if federal power is the storm, state civic infrastructure is the architecture. Some places have lightning rods and reinforced glass. Some places have dry timber and locked exits.

So I’m going back to the sources to trace why some states can improvise democracy under pressure, while others default to deference, silence, or collaboration. (And as Theda Skocpol has argued in a different register, American civic vitality has never been purely local, but shaped by institutions and political opportunity structures that either invite participation or grind it down.)

That’s the journey. Not nostalgia. Not vibes. A map that is drawn from the last time the republic tried to explain itself while it was cracking, so we can recognize what’s happening now, in real time, before the cracks become a border.

It feels like we’re taking a dreadful walk toward a cliff we keep pretending is a hill.

This election cycle isn’t a presidential one, but it can decide the civic fates of so many statewide governing agendas, and of course, the national legislature. And as we encounter news of Steve Bannon reportedly saying that ICE will surround polls this fall, we really have to wonder if we are still lacking the imagination for how far down the rabbit hole we already are, and how the same old political storytellers are still missing the point when diving into polls and focus groups.