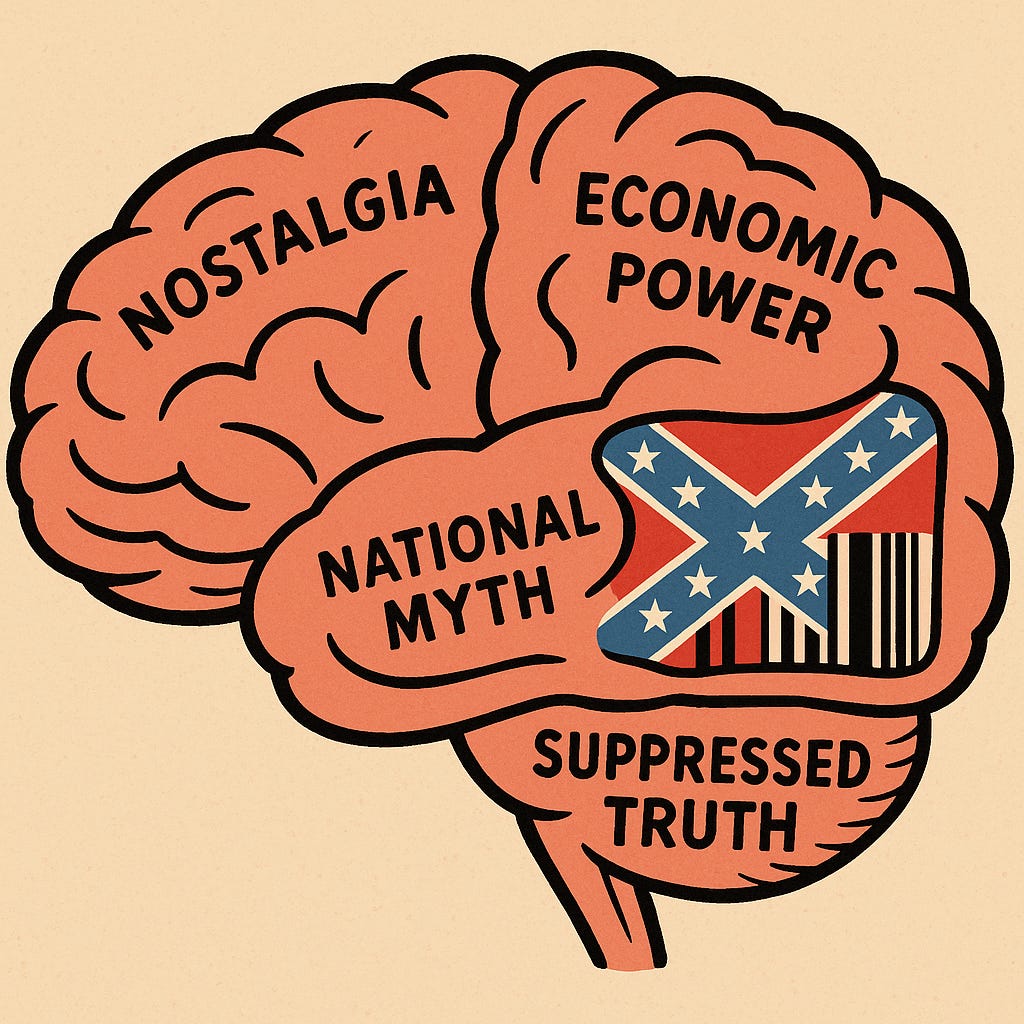

I’ve been thinking a lot about propaganda lately. It’s something I studied intensely in higher education and how it permeates media silos, evolves with technology, and shapes political movements like the New Right into inevitabilities. But propaganda is older than any news ticker or YouTube rabbit hole. It’s about how we tell stories, how we remember, and who gets to forget.

Take the American Civil War.

There are countless narratives floating around today, and their diversity isn’t some accident of free inquiry. For decades after the war, America’s mainstream take on the conflict was that noble men on both sides fought over high-minded disagreements about federalism, tariffs, and states’ rights, not, heaven forbid, over the industrial-scale torture economy of slavery. This sanitized version was no accident either. It was the operational instinct of a traumatized country trying to stitch itself together with a thread of unity that implicitly and explicitly left out marginalized populations.

Enter the Lost Cause: magnolia-scented propaganda that sanitized the Confederacy, erased Black agency, and gave White Southern elites a martyrdom complex instead of a reckoning.

It carved the Civil War into a romance novel with bayonets, where Robert E. Lee was a misunderstood gentleman and not a leader of a rebellion defending human bondage. That ideological machine gave us “Heritage, Not Hate,” rebel flags as fashion statements, and Civil War battle reenactments that somehow always forgot to reenact the auction block.

But here’s the trick: the Lost Cause didn’t just erase the brutal reality of slavery. It also reframed the war through the lens of imperial memory.

And that’s what makes it so enduring, even seductive.