The Country That Wouldn’t Say the Word

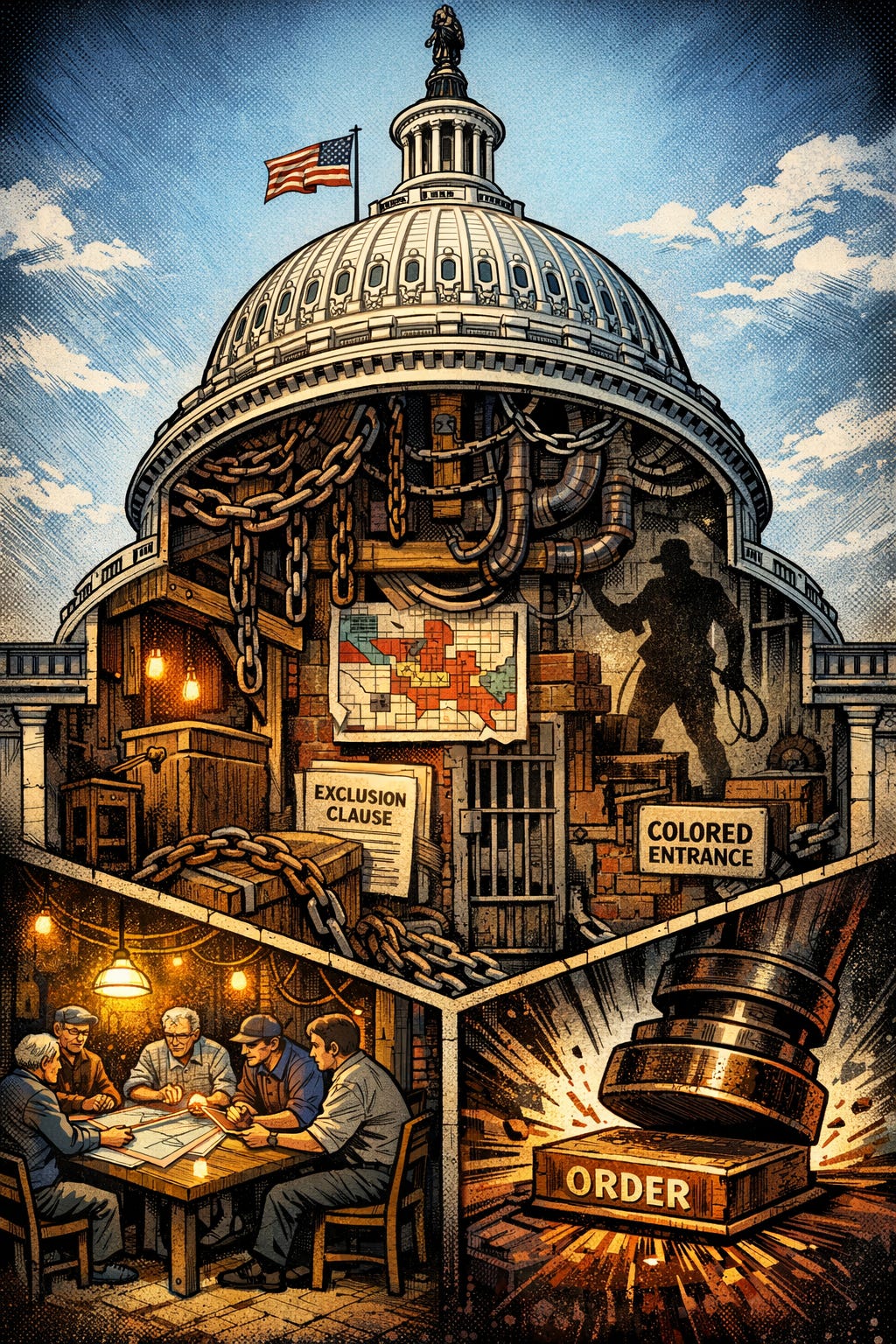

How avoiding race hollowed out the fight for democracy.

As we’ve watched Minnesotans push back against Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) operations, I’ve found myself turning to an older question like what happens when a region becomes a testing ground for the meaning of citizenship? The Midwest was one such laboratory after the Civil War, when Radical Republicans and their allies tried to convert wartime moral energy into Black male suffrage. Those efforts met backlash often ugly and reactionary, but they also reveal something structurally important: in places like Iowa, the political system still had enough pluralism to let democratic reform pass through the pipes. That stands in sharp contrast to the Southern tradition V.O. Key anatomizes, where state politics was routinely engineered to suppress pluralism and small-d democracy rather than channel it.

Robert R. Dykstra and Harlan Hahn’s article, “Northern Voters and Negro Suffrage: The Case of Iowa, 1868,” is valuable because it doesn’t treat Northern states as innocent bystanders to America’s racial order. Instead, it uses Iowa’s referendum politics to show how prejudice, party organization, and perceived economic threat shaped whether equal rights could survive contact with the ballot box.

Just as important, the mechanics of reform mattered as much as the morality. Dykstra and Hahn show how the 1868 push succeeded not by staging a grand national sermon on equality, but by moving through the fine print of state governance. The campaign advanced a constitutional change and, crucially, removed the word “white” from the suffrage language, thus turning what had been an explicitly racial definition of the electorate into a formally universal one. That’s not just a procedural footnote, as it is a miniature version of the American pattern, which progress often arrives through edits and evasions, even through what gets changed on paper, and even when the country still can’t bring itself to say the word out loud.

Drawing on voting returns and the political context around them, Dykstra and Hahn argue that resistance to Black suffrage was not simply “a regional attitude.” It was also tied to status anxiety, especially among voters who felt economically vulnerable and were more susceptible to arguments that Black political rights threatened their own prospects. In other words traveled along material insecurity and partisan incentives. It wasn’t floating in the air.

What makes 1868 stand out is not that Iowa was uniquely virtuous, but that the campaign succeeded in turning rights into law through ordinary democratic mechanisms, such as coalition building, political messaging, and constitutional revision. The outcome matters all the more because Iowa’s Black population was small. That fact strips away one convenient excuse that this wasn’t simply a referendum driven by a large Black electorate. It was, in significant part, a test of whether a predominantly White electorate could be persuaded, however imperfectly, however instrumentally, to expand the circle of citizenship.

This is where the Midwest becomes a useful mirror for the present. A successful rights campaign creates precedent: legal codes, civic expectations, procedural muscle memory. Even when equality is thin on the ground in practice, the existence of an institutional foothold changes what future generations can build on.

Now flip the picture.

In many Southern states, the immediate postwar struggle against political violence and intimidation became a grinding, exhausting war of attrition. Even as mutual aid and survival networks in Black communities strengthened, the broader atmosphere of hostility hardened into an insurgent governance and thus fertile ground for the disfranchising architecture that would later mature into Jim Crow.

We are drifting into an America where federal standards matter less than they used to, or, at a minimum, where enforcement and norms vary sharply once you cross a state line. That makes Reconstruction Midwest history more than an academic detour. It becomes a way to make credible inferences about the present, like if a new federal operation is announced, then what does a state’s institutional memory do with it?

Does it spark mobilization through civic infrastructure and pluralistic habits, or does it slide, smoothly and quietly, into compliance?

It’s notable that the New York Times and even Republicans in Congress had no problem calling out the racist meme that Trump’s official Truth Social account pushed on Thursday night. Plenty of people said the obvious thing out loud (that it was racist) while still wrapping it in the polite alibi that maybe it was a mistake.