The Bombs Are New, But the Logic Isn’t

BONUS: Racist immigration rhetoric for political wins and pardoning root causes after the fact.

The United States is bombing boats in the Caribbean.

Again.

Only this time, there’s no coalition, no congressional theater, no humanitarian fig leaf. We get airstrikes, body counts, and press briefings. These strikes have been framed as a new low under Trump, a descent into barbarism unbecoming of a nation that allegedly invented human rights. But let’s be clear: this isn’t a break from American policy. It’s the continuation of it, just without the window dressing.

The boat strikes are horrifying, yes. They reflect the Trump administration’s obsession with punitive spectacle, where violence isn’t a last resort but the whole point. But violence as policy isn’t unique to Trump, nor is it ahistorical. What we’re witnessing is the unmasking of empire, not its reinvention. For a country that prides itself on a “rules-based order,” the rules have always been negotiable when empire is at stake, and especially when those on the receiving end are poor, racialized, or outside the camera frame.

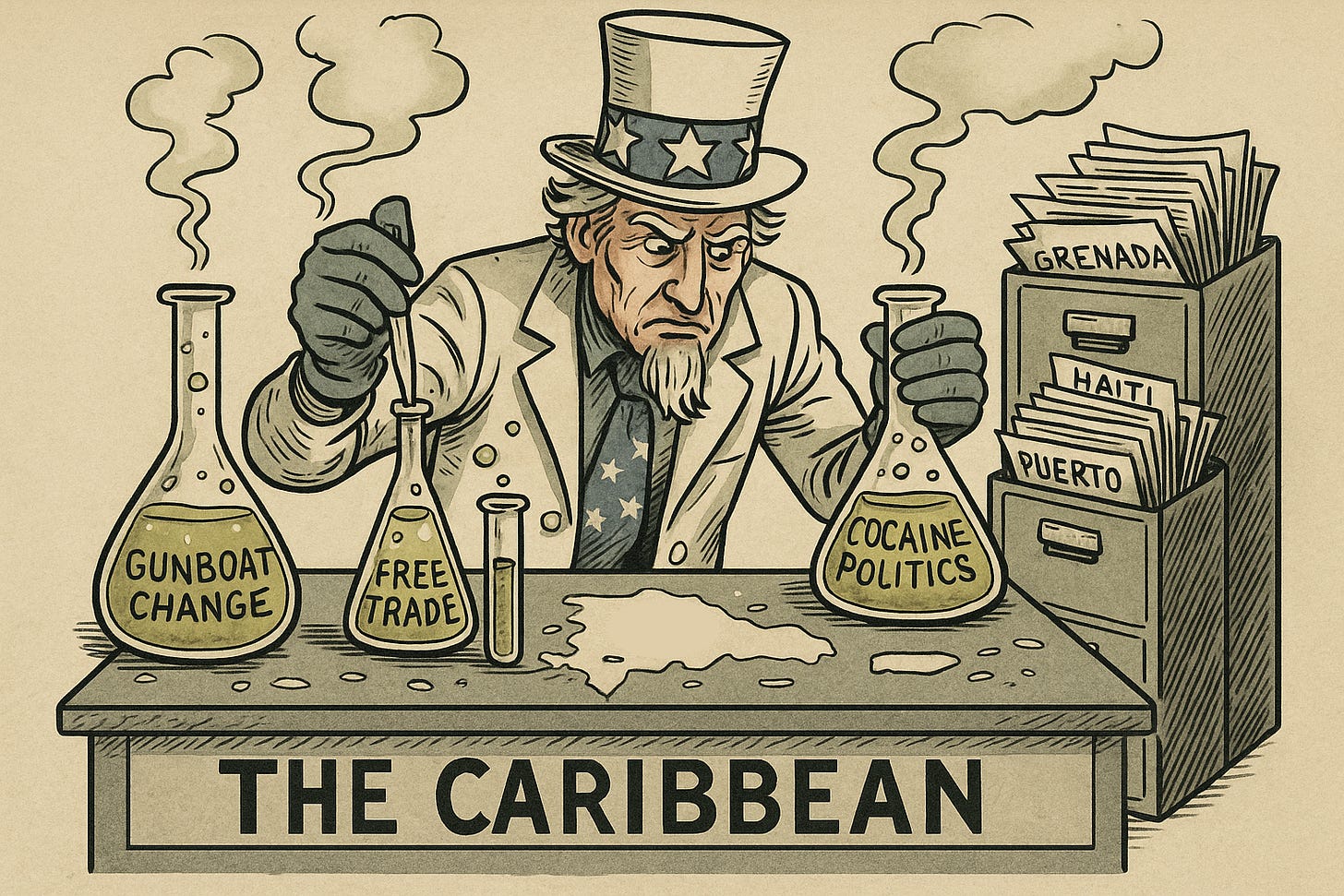

The Caribbean, in particular, has long served as a laboratory for American imperial habits. From the Roosevelt Corollary to the invasion of Grenada in 1983, the region has been treated less like a collection of sovereign nations and more like an imperial backyard, you know, a place ideal for projecting power, testing doctrine, and occasionally bombing things when domestic politics demand a win. The Trump-era strikes aren’t an innovation. They’re a reboot of a very old series, this time with drones instead of destroyers.

But beyond the historical continuity of gunboat diplomacy lies a quieter, more technocratic betrayal, one that scholars like Horace Bartilow have been documenting for years. In Free Trade and Drug Smugglers, Bartilow and Eom analyze how trade openness intersects with narcotics enforcement. Their findings? It depends on your place in the global narcotic supply chain.

For drug-producing nations, trade liberalization can sometimes improve interdiction capacity, as it attracts foreign investment, creates alternative industries, and, in theory, reduces reliance on the illicit economy. But for drug-consuming countries (like the U.S.), trade openness makes interdiction harder. The sheer volume of legal trade overwhelms enforcement systems, and the demand remains insatiable. And for transit countries, especially in the Caribbean, trade liberalization does little. There are no resources for interdiction, no economic transformation, and no structural support…just geography and consequences.

In Bartilow’s terms, the Caribbean occupies a middle position in the “narcotic international division of labor”: not the source, not the consumer, just the corridor. And corridors don’t get investments. They get missiles.

That’s the true obscenity of the current policy. The U.S. exports free trade regimes that destabilize local economies, fuel demand it refuses to manage domestically, and then turns around and bombs suspected smugglers at sea, many of whom may be impoverished fishers conscripted by necessity, not cartel command.

In this context, Trump is not a policy innovator. He’s just saying the quiet part at 120 decibels. Previous administrations cloaked violence in the language of partnership, development, or “regional stability.” Trump drops the euphemisms. He doesn’t need a summit. He has a drone.

When legacy media calls these strikes “a new low,” what they often mean is a more vulgar version of the lows we’ve already normalized. And when centrists call for more arrests instead of airstrikes, they miss the point entirely: the problem isn’t the method of enforcement, it’s the logic that defines enforcement as violence in the first place.

This is the same cycle we’ve seen for over a century: economic extraction, social destabilization, and militarized reassertion of control. It’s just happening faster now, and with fewer metaphors.

Trump’s difference is not that he created the American empire. It’s that he’s shitposting it.

The Harms of Immigration Demagougery

Trump just pardoned the former Honduran president. The same president who, not long ago, was convicted of running Honduras like a narco‑state with a presidential sash. His trial was hailed as a landmark, a rare moment when the U.S. confronted the rot in a regime it had long propped up. And now, with a sweep of Trump’s pen, the conviction is neutralized.

The irony cuts deep. This is the same administration that campaigned successfully by weaponizing American fears about immigration and racialized “chaos” spilling over the southern border. That narrative worked not because it was true, but because it tapped into something older and more potent: the American tendency to see suffering from the Global South not as a consequence, but as an invasion.

Juan Orlando Hernández, once a U.S.-backed darling of the war on drugs, was sentenced to 45 years in a U.S. court for trafficking hundreds of tons of cocaine and for conspiring to use military-grade weapons to do it. But even that mouthful of charges fails to capture the truth: he ruled with impunity, siphoned cartel cash through the state, and unleashed hard state power against the public with Washington’s blessing.