Swing States, Starving Nations

BONUS: How a nation crowned in victory refused to confront its own violence, and exported the consequences.

It’s interesting and also depressing how thousands of voters in the United States can dictate whether aid is withdrawn or continued to nations undergoing famine, civil war, and terrorist insurgencies. ProPublica recently published a report about Trump-era officials celebrating with cake as cuts to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) were implemented during a cholera outbreak in South Sudan. These cuts weren’t only symbolic, but in the tangible world undermined lifesaving emergency response programs during one of the worst cholera epidemics in South Sudan’s history, where civil conflict, famine, and a collapsed health system already threaten the survival of millions.

This follows a broader shift toward transactionalism in U.S. foreign policy, in which humanitarian aid is deprioritized in favor of short-term political and economic interests. Regions like South Sudan, already destabilized by years of conflict, corruption, and foreign interference, are left even more vulnerable when the American aid tap is abruptly shut off. According to ProPublica’s reporting, officials like Peter Marocco and Jeremy Lewin were warned by career experts with decades of field experience that the cuts could create a humanitarian disaster. They went ahead anyway.

Yet the Trump administration returned to the White House a second time, riding a wave of nationalism and grand promises of “America First” and cutting funds to so-called undeserving nations. Campaign rhetoric is often oversimplified, designed for the echo chambers of infotainment rather than the complexities of governing. And yet, it’s enough to convince millions to vote in ways that affect people they will never know or think about. No matter how much scholarship or data might expose the consequences or moral failures of such decisions, it rarely penetrates the information silos built to keep reality at bay.

So we arrive at a moment when global stability rests on the whims of swing-state voters in the Midwest or the Tidewater South. Is it fair to expect voters in Ohio or North Carolina to carry the fate of cholera patients in Juba? Not really. But fairness isn’t the point.

The structure of all this is. And the structure is imperial.

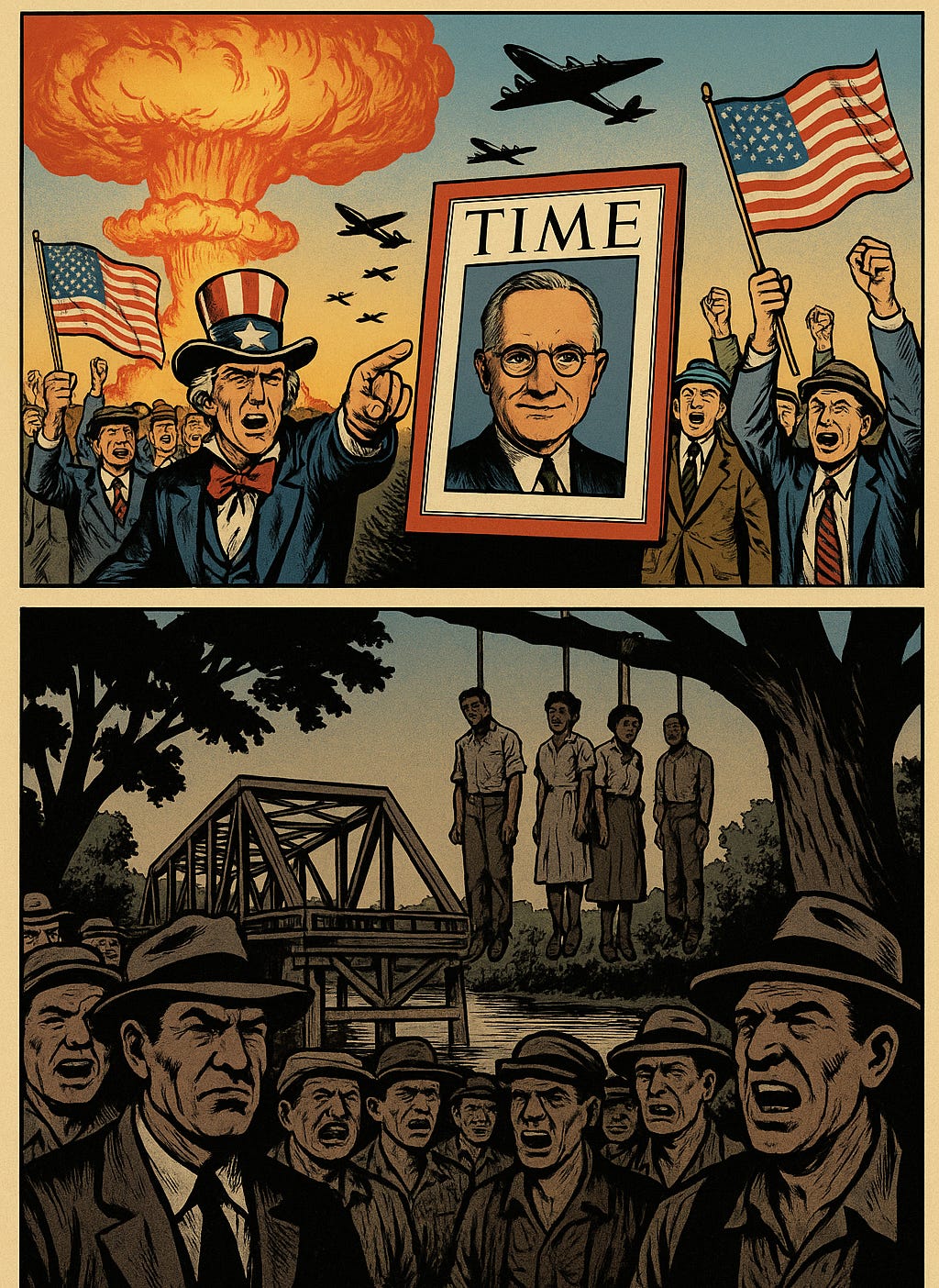

The United States has, for the better part of a century, enjoyed the spoils of global dominance while insulating its electorate from the consequences of that dominance. That’s the bargain.

Our image abroad has long leaned on the myth that we are a pluralistic, open society driven by democratic instincts. Even if that has never quite been reality, it was a story the world wanted to believe after two global wars and the rise of authoritarian regimes. The U.S. cast itself as the anti-fascist lighthouse in a dark sea of totalitarianism. That projection did real work in the world, even if it was more storybook than substance.

But like much of the Trump era, the mask is slipping. And the truth marches outward at a rally, chanting “lock her up.” A global consensus cannot be built on the erratic impulses of a few thousand United States citizens, trained to view the world only through the lens of self-interest and manufactured grievance. The Trump era has not created this condition; instead, it has exposed it. An American electorate grown fat on global wealth but poisoned by its own historical amnesia is capable of extraordinary cruelty dressed up as populist redemption.

We are no longer a reliable partner. And the tragedy in South Sudan is not an isolated incident. It is a case study in what happens when a superpower’s moral center collapses under the weight of its own illusions.

A Nation Unseasoned by History

Oftentimes, I think of the story of the United States as one where a nation with a short history, still reeling from its founding hypocrisies and the fractures left unhealed, suddenly gains the keys to the world. It’s like handing a trust fund baby the keys to the school after he turns 18. The United States, which ascended to global power just decades after erupting in a brutal civil war, never truly reckoned with its inextricable connection to racial brutality and economic domination. It was still a young nation in the grand sweep of world history, unseasoned in the brutal art of constitutional reinvention and national transformation, and yet, it was all-powerful.