Author’s Note: Apologies for the late newsletter today! I celebrated my birthday by having a slower morning. Those are rare and a blessing. But I present to you today’s edition of Stew On This. Enjoy and remember to spread love. That’s what is important because the world keeps spinning, no matter how insane it continues to become.

At the recent UN Climate Conference (COP), South Korea announced a major step in its energy transition: the phased shutdown of 40 out of its 61 coal power plants by 2040, with a final decision on the remaining 21 expected in 2026. Seoul, walking the increasingly narrow tightrope between energy security and climate leadership, framed this as a necessary evolution for a developed democracy in a warming world.

Across the Pacific, its closest ally appeared to drift in the opposite direction. The United States, under the specter of Trumpism and a Republican resurgence, has revived talk of a coal renaissance. The GOP campaign machinery sells it as energy independence, while critics call it economic necromancy. Washington’s leadership on climate, already bruised by its withdrawal from the Paris Agreement under Trump, now faces renewed questions of credibility.

This rift isn’t just environmental. It reflects a deeper unraveling of America’s global posture. While South Korea leans into multilateral commitments, the United States seems intent on retreating behind its own borders, weaponizing aid, and hollowing out the soft power structures it once championed.

This tension surfaced again in October, when North Korea denounced a U.S.-South Korea agreement to develop nuclear-powered vessels. The outrage from Pyongyang was expected. What followed, less so: American officials privately shrugged off the diplomatic cost, signaling a shift toward transactional realism over norm-setting diplomacy.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the sustained cuts to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The Biden administration had already proposed trimming its foreign aid budget, but under Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who is a hypothetical but increasingly plausible figure in a post-2024 GOP administration, those cuts have become ideological. Rubio has lambasted what he calls the “NGO-industrial complex,” accusing aid organizations of fostering dependency and hostility toward U.S. interests. He’s even cited UN voting records to argue that American taxpayers are funding governments that vote against Washington.

But this isn’t just domestic political theater. A new study by the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal), currently under peer review, estimates that dramatic aid cuts by the U.S. and its European allies could lead to up to 22.6 million excess deaths in 93 low- and middle-income countries by 2030, including 5.4 million children under five. Even moderate reductions would mean 9.4 million additional deaths. The study uses counterfactual mortality modeling to assess how reductions in health spending, education, and social services, previously propped up by aid, might affect survival rates.

Critics argue the models oversimplify causality. But supporters point to real-world patterns: from HIV antiretroviral access in Sub-Saharan Africa to vaccine campaigns across Southeast Asia, Western aid has historically filled public health gaps that local systems could not. Its sudden disappearance won’t go unnoticed—or unpunished.

In geopolitical terms, this amounts to strategic self-harm. Foreign aid is not just benevolence; it’s also influence, alliance-building, and legitimacy projection. The Marshall Plan didn’t just rebuild Europe; it bought loyalty, markets, and a liberal order. Cutting aid now, in an era of rising Chinese and Gulf state influence, concedes terrain in a soft power war the West cannot afford to lose.

The story of U.S. aid since 1945 is a story of evolution and erosion. From postwar reconstruction to Cold War alignment, from structural adjustment in the 1980s to global health in the 2000s, aid has always served dual purposes: altruism and advantage. But beginning with the Nixon shock of 1971, the Volcker-induced interest rate hikes of 1979, and the neoliberal turn of the 1980s, American leadership has become increasingly mercantile. Bretton Woods ideals gave way to bond markets and austerity, and with them came diminished patience for global responsibility.

Today, we see the consequences. The U.S. says it’s prioritizing hard power over handouts. Its European and East Asian allies, no longer able to rely on American stability, are rearming and redirecting funds once destined for development. In this vacuum, powers like China step in, not necessarily with the same norms, but often with fewer questions.

Observers are split. Some see the aid rollback as a betrayal of the postwar promise, or the moment the West finally broke its own myth. Others, more realist in posture, argue this is simply the world reverting to mean: states pursuing interests, not ideals.

But even the realists must admit that the world doesn’t forget who shows up in times of need. Nor does it forget who walks away.

The American century may not end with a bang or a wall. It may simply end with a budget cut, a shrug, and a silence where leadership used to be.

What Trump 2.0 Continues to Reveal

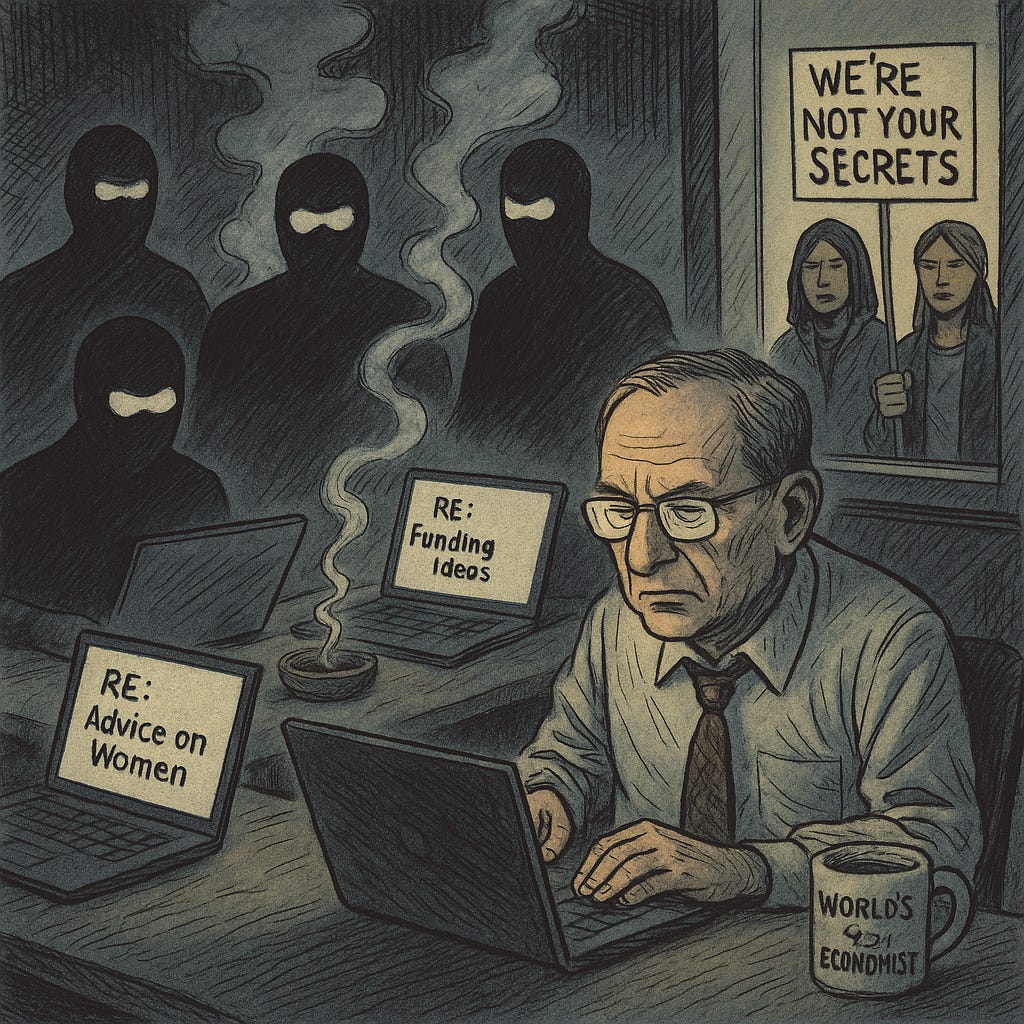

I’ve written plenty about what the second coming of Donald Trump reveals about America and the political class that delivered us here. But another wave of post-2024-election realism hit me this week, courtesy of the revelations about former Harvard president and economic oracle Lawrence Summers. The man who once lectured the world on rational markets and efficient governance is now stepping away from public life, not because of a failed policy or a controversial op-ed, but because of a long and cozy relationship with Jeffrey Epstein that extended years after Epstein’s conviction as a sex offender.

The latest email dump is stomach-turning. Summers didn’t just know Epstein; he sought his advice on women, money, and international connections well after Epstein’s crimes were public knowledge. At one point, he even joked about Epstein funding his wife’s theater program. This wasn’t just bad judgment. It was a window into the social ecology of elite impunity. And it reveals something crucial: the Epstein files aren’t just about Trump. They’re about an entire ecosystem of powerful men who either partook in or enabled abuse, while others in their orbit chose silence because their hands were busy feeding at the same trough.