Nothing Here Looked Like Conflict

Growing up Black in a Baltimore in a way that didn't fit the stereotypes.

Today’s post will be a little different.

It’s already been a tumultuous thirteen days to start the new year of 2026, so rather than diving into the latest current events and historical currents, I want to share something more personal, a journal entry drawn directly from my own life.

One of the peculiarities of growing up in Baltimore, but within the relatively stable outer-borough life of Ashburton, was how insulated it felt. Ashburton existed as a small hamlet outside the rest of the city, yet was shaped by its deeper histories. The neighborhood once enforced a racial covenant in its housing codes, explicitly barring Americans of color from purchasing homes.

Ashburton was primarily occupied by Jewish American immigrants, people deeply familiar with exile, displacement, and discrimination. Many were strident allies in the struggle to uplift Black Americans, recognizing parallels in diasporic histories marked by exclusion and survival. When Jewish families sold homes to Black families like mine in the 1960s, they helped create a modest but meaningful pocket of Black middle-class life in Baltimore. My grandparents, my parents, my sister, and I grew up inside that inheritance.

My parents worked across both the private and public sectors, themselves the children of Black educators. My paternal grandfather held a Master’s degree from Johns Hopkins University and was part of the effort to desegregate the teaching staff at Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, one of Baltimore’s premier magnet high schools.

I’ve been thinking about legacy more than I used to, especially since the Trump sequel began. For a long time, I overlooked it. Comfort has a way of dulling historical awareness. Private Catholic schooling, friends whose lives ranged from solidly middle class to unmistakably opulent, and a culture of consumer abundance and immediate gratification that made it tempting to believe race no longer mattered in this “new” America.

Martin Luther King Jr. was heavily marketed to my generation as a sanitized national icon, not the disruptive figure he was widely understood to be when my father was coming of age. It was easy to believe the country had already settled its moral accounts.

Life moved on.

I attended Mount Saint Joseph High School in Baltimore and later the University of Maryland at College Park after a competitive admissions process, choosing in-state tuition as college costs skyrocketed. I spent years as a wandering Terp, disillusioned by my own lack of direction and by the journalism path I had set for myself since middle school.

I overindulged in substances to dull the discomfort of emotional confusion. What saved me was love. My parents, my siblings, close friends, and history professors who believed in my curiosity about humanity’s story and recognized real inquiry beneath the haze. Switching my major from journalism to history changed my trajectory. and I formed one of the most important friendships of my life, one that allowed me to see the world not only as an American minority but as part of a global one. In many ways, I was saved from myself by the care surrounding me.

After college, my body forced a reckoning. I was diagnosed with avascular necrosis in both hips. From 2017 to 2020, I walked with a cane before eventually undergoing bilateral hip replacements. The pain was real, and so was the temptation to disappear into an opioid fog.

I didn’t. My mother’s resolve wouldn’t allow it. She pushed me into physical therapy and insisted that this wasn’t the end of my story but the beginning of a harder, truer chapter. During that period, I was accepted into a Master’s program in Political Communications at American University. I found myself increasingly on Twitter, waking up at 5 a.m. each morning to respond to the next unhinged Trump tweet and debating whether he was an aberration or the natural culmination of American conservatism.

In those daily exchanges, I encountered curious, serious writers who treated disagreement as inquiry rather than sport, like Charlie Sykes , Charlotte Clymer, Jim Swift, Jonathan V. Last, Madeline Peltz, Marlon Weems, Parker Molloy, Noah Berlatsky, Keith Boykin, Melissa Jo Peltier, Stuart Stevens, and Aaron Rupar. Many of whom were also building their own Substacks and theories. Those conversations sharpened my thinking and reminded me that intellectual life can still be generous, even in unforgiving digital spaces.

My time at Media Matters for America coincided with the pandemic, my parents’ divorce, earning a grad degree, and recovery from my second hip replacement. Watching the far-right disinformation pipeline flow seamlessly into mainstream media, while the country unraveled under racialized lies, became suffocating. The despair wasn’t abstract; it was personal, national, and relentless.

Eventually, the pandemic ended. So did that chapter of my life. What followed were experiences that widened my perspective and restored my sense of movement: working with brilliant minds at the Bank Information Center, traveling to Togo and Benin, teaching middle schoolers at Parkville Middle School, and collaborating with remarkable people at the Congressional Award. Each role added texture, humility, and renewed belief in collective effort.

That brings me to today.

I started this newsletter in 2022 as a way to process my post–January 6 disillusionment and anger, especially watching Fox News and Alex Jones mock Black Americans daily with little pushback from institutions that claimed responsibility and restraint.

What began as a personal outlet has become something sturdier. This space has grown into a place to challenge priors, publish deeply personal essays like this one among trusted readers, and examine how history and current events braid together. It has also convinced me that the communications world desperately needs more historical analysis and less reflexive sloganeering about American exceptionalism.

If you’ve made it this far, thank you. If you were looking for straight news analysis, I point you to my essays yesterday on the investigation into Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell and the instability in Iran.

Your support has made a real difference in my life.

After spending much of the 2020s in a spiral of self-doubt, the effort to build this publication and a daily, engaged readership has grounded me in ways I still struggle to articulate.

All the best,

Steward

The Bigotry Many Learned to Live With

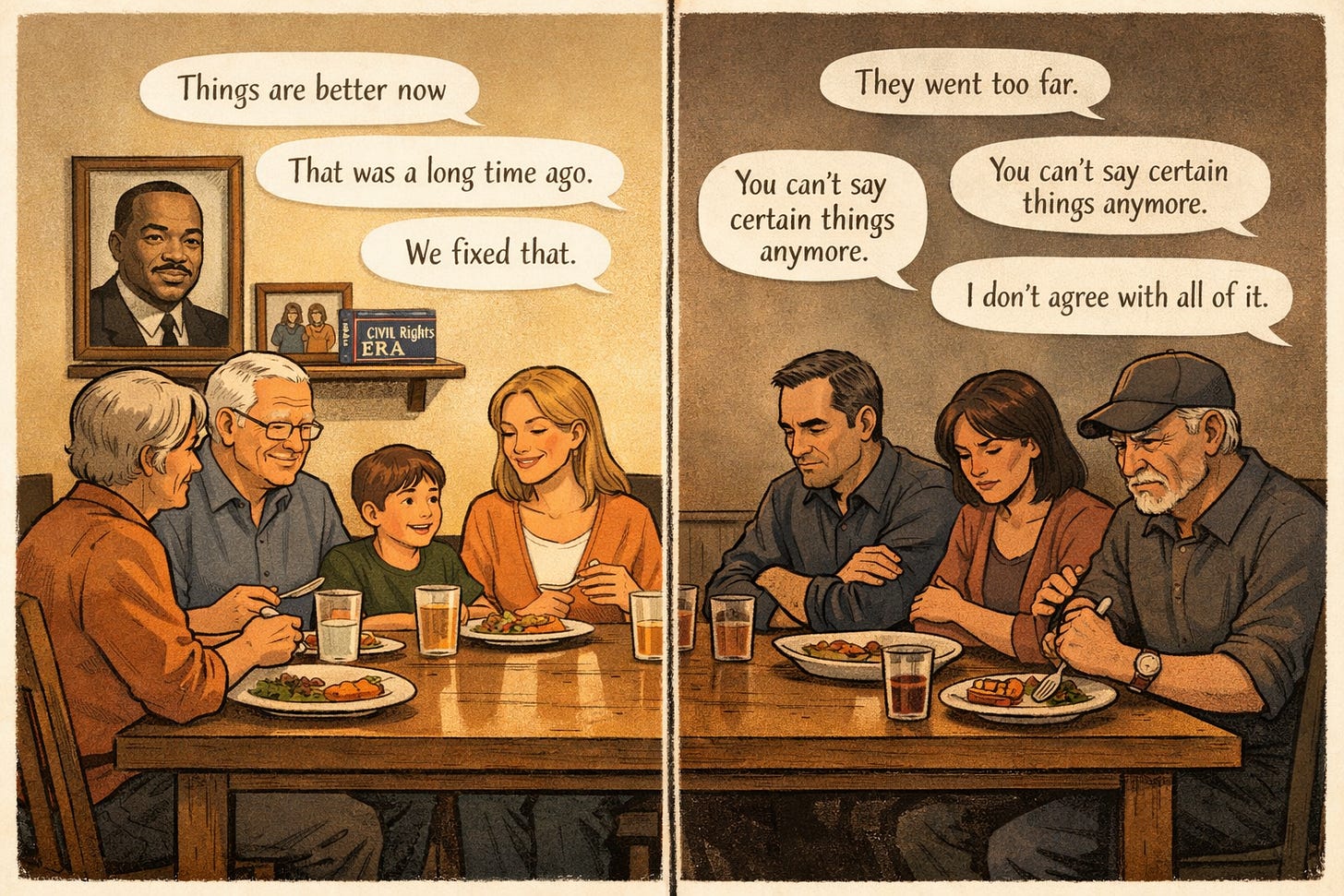

Growing up, we were taught to look at the 1960s as an almost otherworldly time, when Black Americans were sent to the back of the bus, spat upon, and could fear for their lives simply for looking the wrong way. To many of my White counterparts, those fears sounded exaggerated, even irrational, because they believed people simply couldn’t be that racist. The assumption was that such cruelty belonged to a bygone era.

I don’t think that belief was always rooted in malice. Often, it came from distance, from never having lived with that kind of fear, or from wanting to believe that moral progress, once achieved, maintains itself. There was comfort in imagining that the country had already settled its most painful moral questions, that the civil rights era represented a decisive turning point rather than an ongoing obligation.

What I’ve come to understand more clearly with time is that this optimism, however sincere, depended on overlooking something uncomfortable: not everyone accepted the conclusions of the civil rights project. Some resisted openly, but many more simply withdrew. They reorganized their lives quietly, into homogenous neighborhoods, private institutions, coded political language, and social arrangements that allowed old hierarchies to persist without open confrontation.

A paid subscription gets you:

Full access to the archives

The ability to comment and join the conversation

Stew’d Over, and other bonus daily newsletters!

Live Ask Me Anything sessions with paid readers