Modernism, Postmodernism, and the American Mind

Why our civic life shifted from certainty to suspicion, and what’s left in the ruins of truth.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the academic concepts and differences between modern and postmodern. They aren’t just ivory-tower labels; they’re two different ages in the American experience. We are living in the zenith of the latter, whether we like it or not. These terms can help us track shifts from literary tones to psychosocial behaviors, from how we tell stories to how we govern. They explain our civic evolutions and our loss of a shared truth.

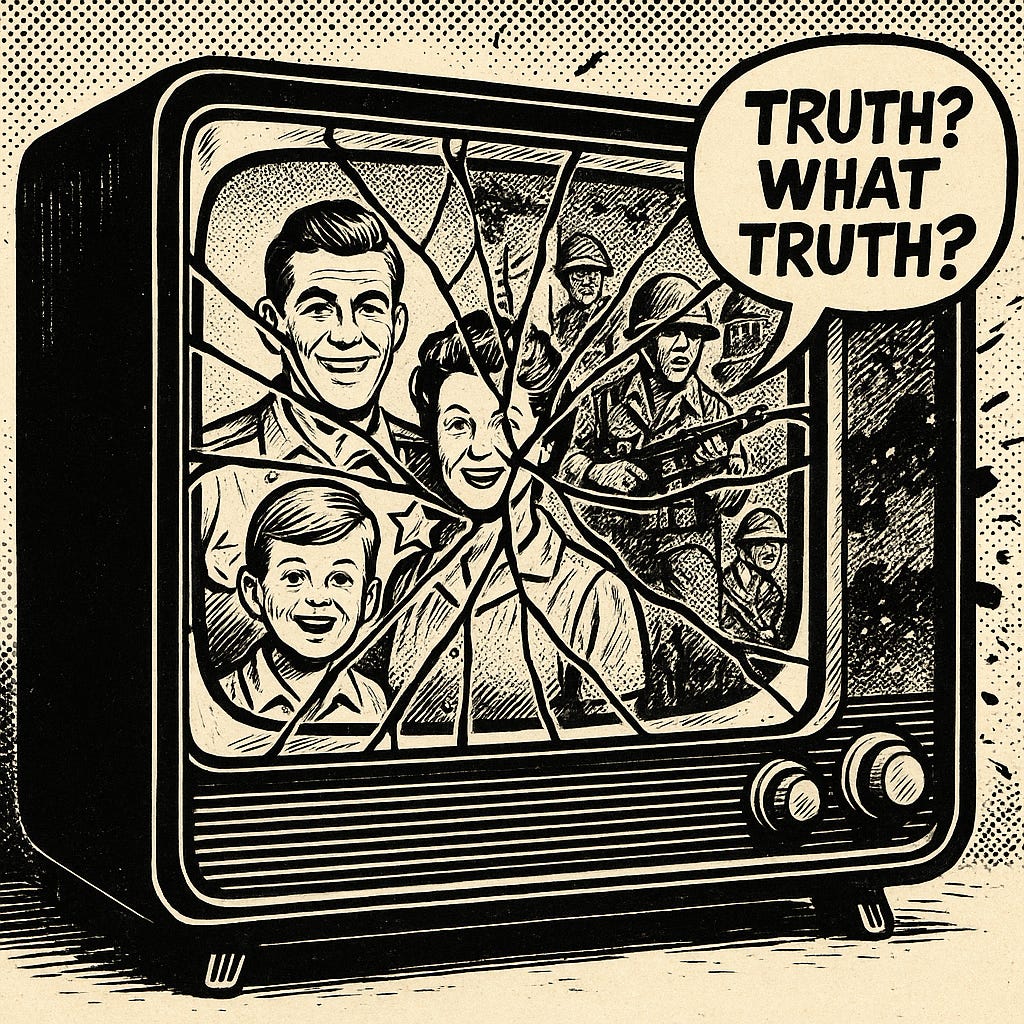

Today, we inherit a landscape where fragmented media ecosystems allow people to believe not just their own opinions but their own “facts.” Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s old line, “You are entitled to your own opinion. But you’re not entitled to your own facts,” landed right at the cracking open of the postmodern age. For our purposes, the difference between modern and postmodern comes down to how the public views public life and civic purpose.

Take Ronald Reagan: his enduring appeal rested on a set of half-truths about government waste and inefficiency. Those half-truths worked because the public had already soured on government after watching it abuse its authority through surveillance, bloated bureaucracy, and ill-conceived wars. Modernism gave us faith in rational planning and centralized authority; postmodernism gave us suspicion that those very tools were corrupt, cynical, or worse.

Jonathan Rauch recently offered his own genealogy of premodernism, modernism, and postmodernism. He sketches them neatly:

Premodernism: faith, hierarchy, divine truth.

Modernism: reason, evidence, order.

Postmodernism: suspicion, power, narrative.

It’s tidy, even elegant. A good scaffolding.

But scaffolding isn’t the house.

When Rauch applies that framework to the American Right, he falters. He argues that Trump’s conservatives borrowed postmodern tactics from the Left, as if skepticism and spectacle suddenly drifted across the aisle like pollen. That’s too clean. The Right didn’t need to borrow; it had been marinating in its own brand of postmodernism for decades.

Distrust of government? That was gold-plated by Barry Goldwater. Conspiracism? Practically a cottage industry by the time Reagan was cracking jokes about “nine most terrifying words in the English language.” Grievance as glue? A national pastime since the backlash to Civil Rights reforms, when drained-pool politics and gated neighborhoods turned separatism into suburban normalcy. These weren’t tactical imports, but homegrown responses to a nation where Mayberry myths no longer held.