Christmas Strikes in Nigeria

From prophetic fear to permanent war: tracing the strange theology of American power, from Strauss to the Sahel.

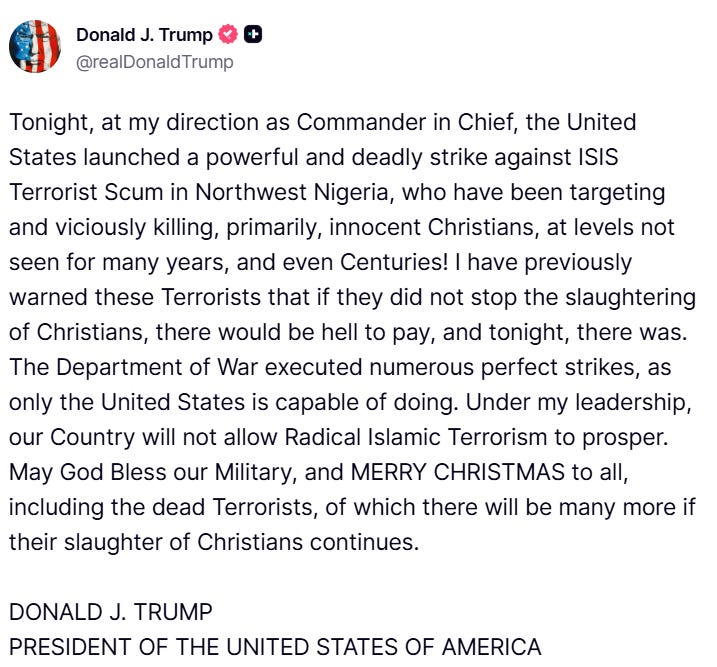

Last night, President Trump announced in his signature fashion that the U.S. had conducted airstrikes against ISIS targets in northwestern Nigeria. He fused patriotism, religious liberty, and civilizational rhetoric, framing the strikes as a defense of persecuted Christians. Nigeria’s Foreign Minister confirmed that the strikes were carried out in coordination with the U.S., under a preexisting intelligence-sharing and security cooperation framework.

But the narrative that Christians are uniquely or singularly targeted in Nigeria, while politically effective, is at best a half-truth. NPR’s Emmanuel Akinwotu reports from Benue State, which is a region often dubbed Nigeria’s breadbasket, and revealed that the violence afflicting farming communities is deeply tied to resource conflict. Herders, many of whom are Fulani and Muslim, need grazing land for their cattle. Farmers, predominantly Christian, need land for their crops. Climate change, population growth, and land degradation have turned what were once localized disputes into large-scale violent clashes. Terrorist groups like Boko Haram and the Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP) have exploited this chaos, piggybacking on grievances to pursue broader agendas. But to reduce this to a simple Christian-versus-Muslim genocide ignores the structural realities and intercommunal complexities driving the conflict.

To understand the gravity of this U.S. strike, it helps to step back and consider the historical arc of Nigeria–U.S. relations. As historian John Ayam has documented, the U.S. relationship with Nigeria has long been marked by a mix of cooperation and caution. After independence in 1960, the U.S. provided generous economic aid but kept Nigeria at arm’s length during the 1967–1970 civil war, treating it as a British sphere of influence. The U.S. imposed an arms embargo and limited itself to humanitarian assistance, prompting Nigeria to turn to the Soviet Union for military support.

Tensions flared again in the 1970s when Nigeria recognized the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) in Angola, clashing with U.S. Cold War priorities. The Ford administration flagged Nigeria’s actions as undermining American influence in Southern Africa. Yet, despite diplomatic strain and periodic sanctions, particularly during Nigeria’s periods of military dictatorship and human rights abuses, economic ties between the U.S. and Nigeria, especially around oil, remained remarkably resilient. By 1974, U.S.–Nigeria trade reached $1.65 billion, largely driven by energy exports. Even after the 1993 annulment of democratic elections and subsequent sanctions, U.S. oil imports from Nigeria continued largely uninterrupted.

The return to civilian rule in 1999 under President Obasanjo was a watershed, but democratic stability has proven elusive. As ACLED’s data on the 2023 election shows, political violence remains a feature of Nigeria’s democratic process. The lead-up to that election saw nearly 100 politically motivated deaths, targeting candidates, electoral officials, and civilians. Hate speech and digital incitement, as analyzed by Matthew Alugbin of the London School of Economics, turned the electoral campaign into an ethnic and religious minefield. Political language became weaponized, with major figures invoking tribal grievances and religious identity to mobilize voters, as well as intimidate opponents.

So when U.S. airstrikes occur on Nigerian soil, on Christmas Day, no less, they cannot be seen in isolation. Nigeria is not a failed state but a sovereign regional hegemon with an operational government, military, and diplomatic presence. This marks the first time the U.S. has conducted publicly confirmed lethal airstrikes in a functioning African state that isn’t a warzone or a collapsed entity.

This is not Somalia, Yemen, or Libya.

Nigeria has not forfeited sovereignty, and yet the U.S. has now exercised force within its borders.

Yes, the Nigerian government consented. But how that consent was negotiated matters. There was no formal joint announcement, no pre-coordinated messaging. Instead, Trump took to social media with theatrical flair, proclaiming victory over “ISIS terrorist scum” and extending a “Merry Christmas… even to the dead terrorists.” Nigeria’s later confirmation framed the operation in more neutral terms, which avoided religious language and emphasized broader security cooperation. This divergence in framing suggests that Nigeria’s consent, while real, may have been less about partnership and more about political calculus.

Maybe that was the point. The element of surprise. A display of American global reach dressed in campaign colors. But the questions remain. Have we entered a new era where the U.S. strong-arms partners into allowing kinetic operations under the veil of consent? Where holidays are turned into stages for military drama? Where regional powers are treated like client states?

And what comes next? The airstrikes, while tactically successful, do not dismantle the networks of violence and terror that entrench themselves in rural Nigeria. Will innocent bystanders emerge from the rubble? Will this embolden ISWAP further, allowing them to claim moral victory in the propaganda war? Or will it degrade their operational capacity meaningfully?

It’s hard to say.

Maybe the Trump administration made a bold strategic move that deserves recognition, however garish the packaging. Or maybe this was another erratic maneuver by a Department of Defense untethered from long-term strategy. But the rest of us would do well to stay informed, because what happens in Sokoto this week could echo far beyond Nigeria’s borders.

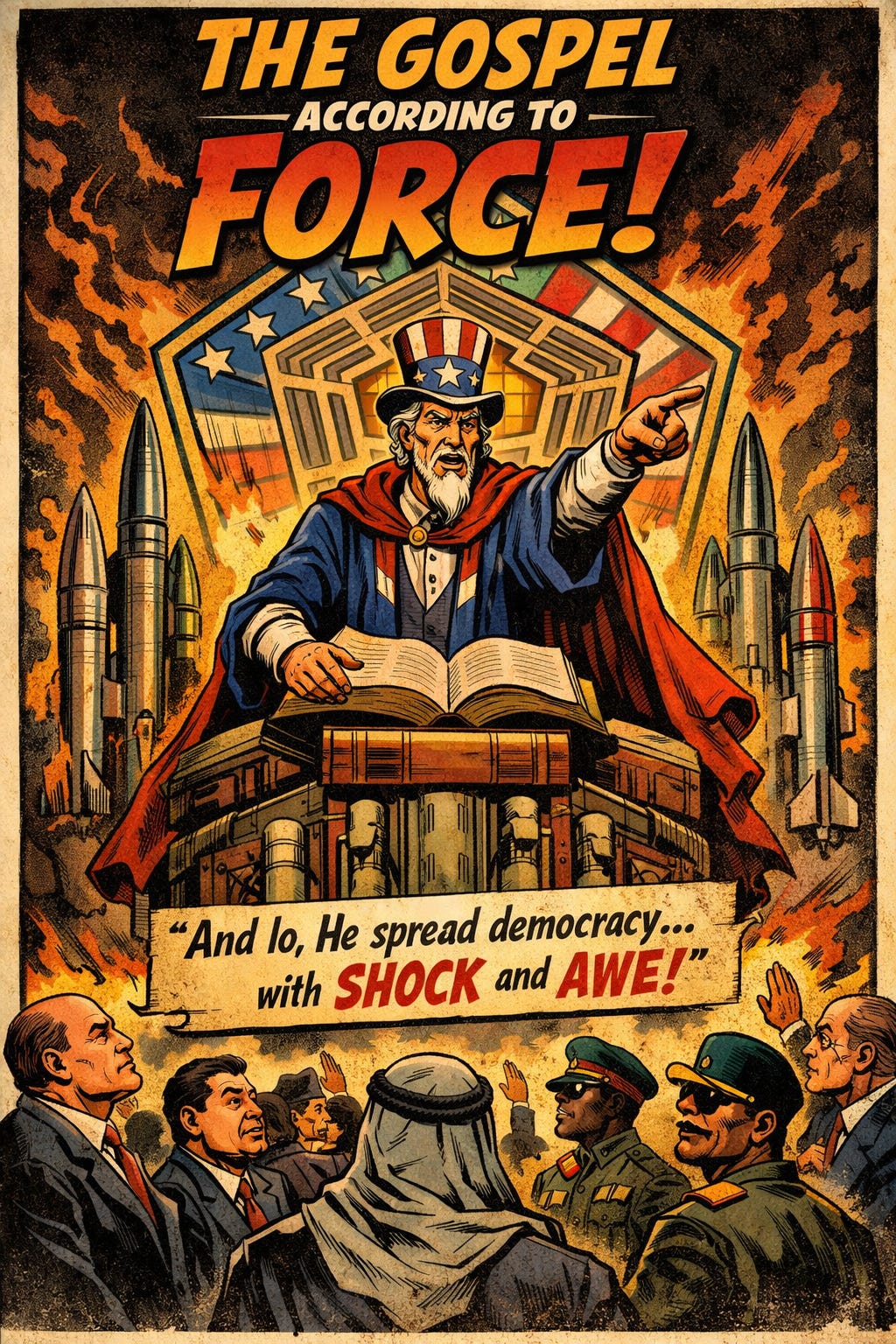

The World that Neoconservatism Knowingly (and possibly unknowingly) Built

It is staggering to watch the evolution of America’s War on Terror, from the end of the Cold War, through the flashpoint of 9/11, and now to U.S. airstrikes in northwestern Nigeria. What began as a response to a singular trauma has matured into a standing global doctrine, one that authorizes force far from declared battlefields and long after the original perpetrators of 9/11 are gone.

The Power of Nightmares, the BBC documentary series by Adam Curtis, is something I first watched in high school toward the end of Obama’s first term. Its core claim is not that terrorism is fake or that neoconservatives are cartoon villains, but that modern politics increasingly runs on constructed narratives of fear. Curtis argues that radical Islamist movements and American neoconservatism, despite being ideological enemies, fed off a shared diagnosis. One that believes that modern liberal societies are decadent, hollow, and lacking purpose.

This critique is often linked to Straussian thought, though usually in a distorted way. Leo Strauss, a German‑Jewish émigré and political philosopher, was deeply concerned with the fragility of liberal democracy. He believed modern societies had lost confidence in moral truth and civic virtue, and he warned that relativism could corrode political order. Strauss emphasized careful reading of classical texts, the tension between philosophy and politics, and the need for regimes to sustain shared myths or civic ideals. He did not advocate deception in the crude sense often attributed to him, nor did he outline a foreign policy doctrine. But some of his students and intellectual descendants interpreted his concerns as a warning that societies without a unifying purpose drift toward nihilism.