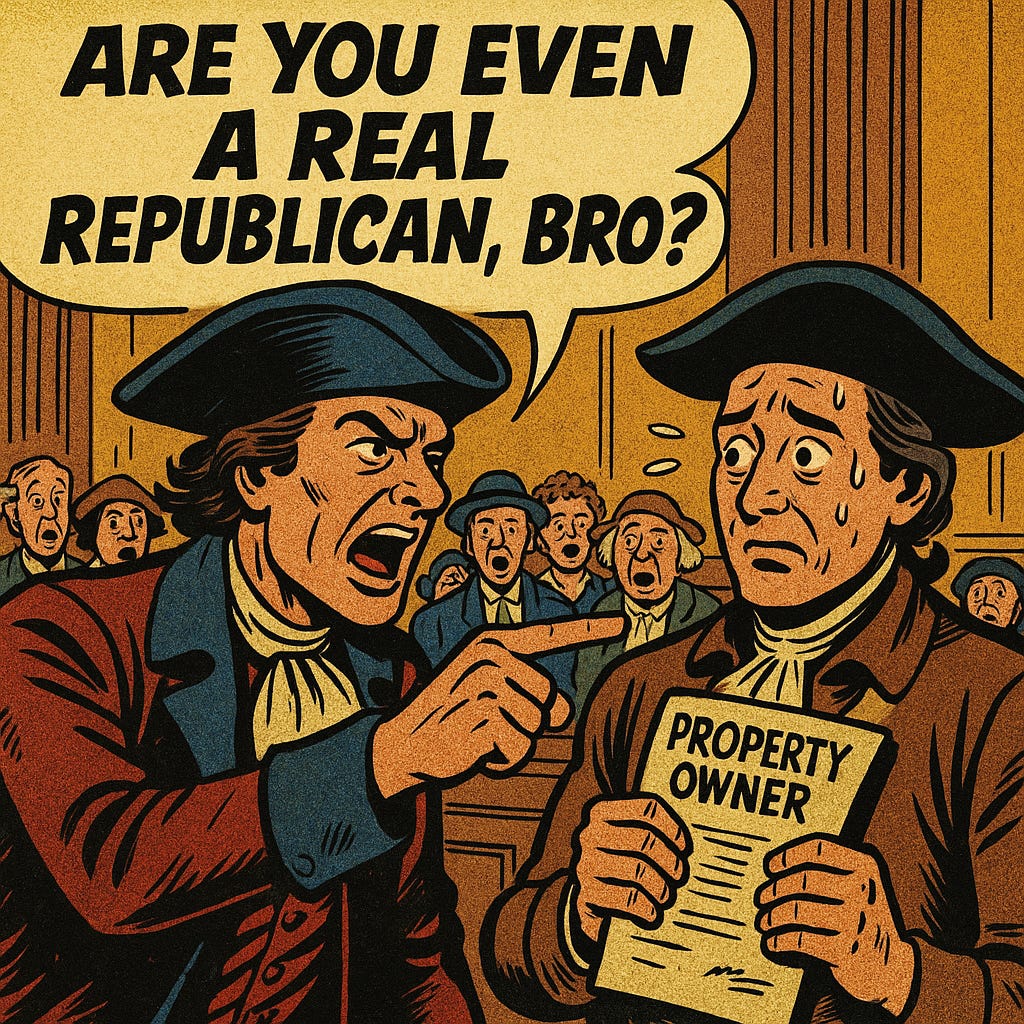

America’s First RINO Hunt (Empire of Liberty #12)

The playbook hasn’t changed, only the hashtags have.

Gordon Wood’s Empire of Liberty captures something essential about the early republic: democracy wasn’t a settled fact, but an argument in motion. Every institution, from federalism to the courts, and even the Constitution itself, was a contested stage on which the young nation argued about what self-government meant. Nowhere was that contest sharper than over the judiciary. Today, courts rely heavily on common law traditions, such as the doctrine of stare decisis, which treats precedent as binding. However, in the 1790s and early 1800s, Americans were uncertain whether English common law was a treasured inheritance or a monarchist relic that had been smuggled into republican soil.

The Judiciary Act of 1789 established the framework for a three-tiered federal court system, comprising district courts, circuit courts, and the Supreme Court perched on top. Federalists saw it as a ballast for a steady anchor for the republic’s shaky hull. Republicans, however, saw something more sinister: a hidden fortress of unelected lawyers in black robes, ready to shield privilege and property against the people’s will. The tension flared almost immediately.

In Chisholm v. Georgia (1793), the Supreme Court ruled that citizens could sue states in federal court. To Federalists, this was common sense: if states could violate contracts or debts with impunity, the union was a sham. However, in states like North Carolina, it was perceived as judicial tyranny. Allowing private suits against sovereign states felt like shackles on state independence, a violation of that revolutionary promise of self-rule. The backlash was so fierce that Congress rushed through the 11th Amendment, which stripped the Court of that jurisdiction. Ratified at lightning speed, the amendment was the first direct slap on the judiciary’s wrist. It was also a reminder that even at its birth, the Court’s authority rested on shaky democratic ground.

Fast forward a few years, and the judiciary remained a battlefield. The Federalists, battered by their own mistakes, such as the Alien and Sedition Acts and the handling of the Quasi-War with France, were losing public support. Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans thundered against them as monarchists in disguise. Then came the fateful election of 1800, the so-called Republican Revolution. Jefferson’s victory was not just about policy; it was about capturing the mantle of democracy itself. And for Jefferson, that meant “republicanizing” the court, or purging them of Federalist entrenchment and making it accountable to the people.

But the Federalists were not about to hand over the keys. In his final weeks, John Adams launched a parting barrage: the “midnight judges.” With Congress’s help, Adams filled judicial vacancies with loyal Federalists, hoping to salt the earth before Jefferson could plant his own crops. At the center of this last-minute maneuvering was John Marshall, elevated to Chief Justice, a man whose staying power would haunt Jeffersonian dreams for decades. It was high drama: Adams furiously signing commissions in the dead of night, Jefferson storming into office declaring a democratic mandate, and the judiciary suddenly cast as the last Federalist redoubt.